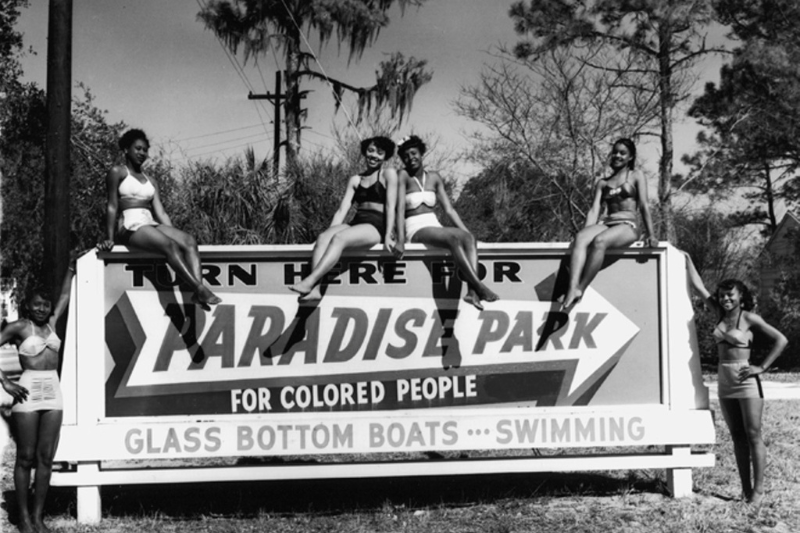

From 1949 to 1969, Paradise Park became one of the country’s most popular places for Black vacationers. Photos courtesy of Florida Memory

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

CLEARWATER — In the middle of the last century, African Americans had limited options for visiting tourist spots in the Jim Crow era South. White entrepreneurs Carl Ray and W.M. “Shorty” Davidson decided to carve out a place downriver called “Paradise Park for Colored People,” and from 1949 to 1969, this park — managed by boat captain Eddie Vereen — became one of the most popular places for Black vacationers in the country.

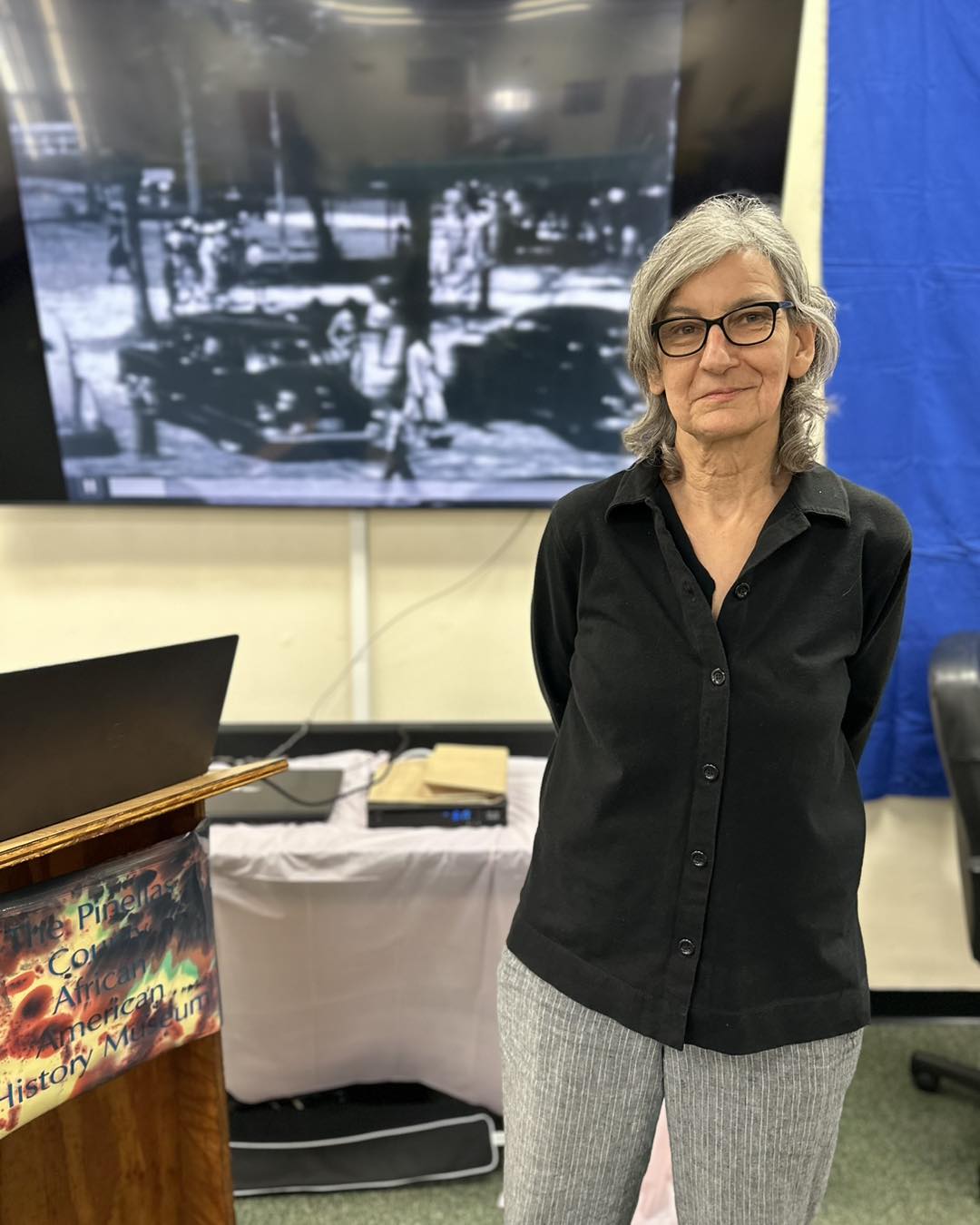

Florida author Lu Vickers discussed this historical site explored in her book, co-authored with Cynthia Wilson-Graham, “Remembering Paradise Park” in March at the Pinellas County African American History Museum.

“Water was contested,” Vickers stated, noting that during segregation, beaches and lakes were often divided into white and Black areas if they were not outright off-limits to African Americans.

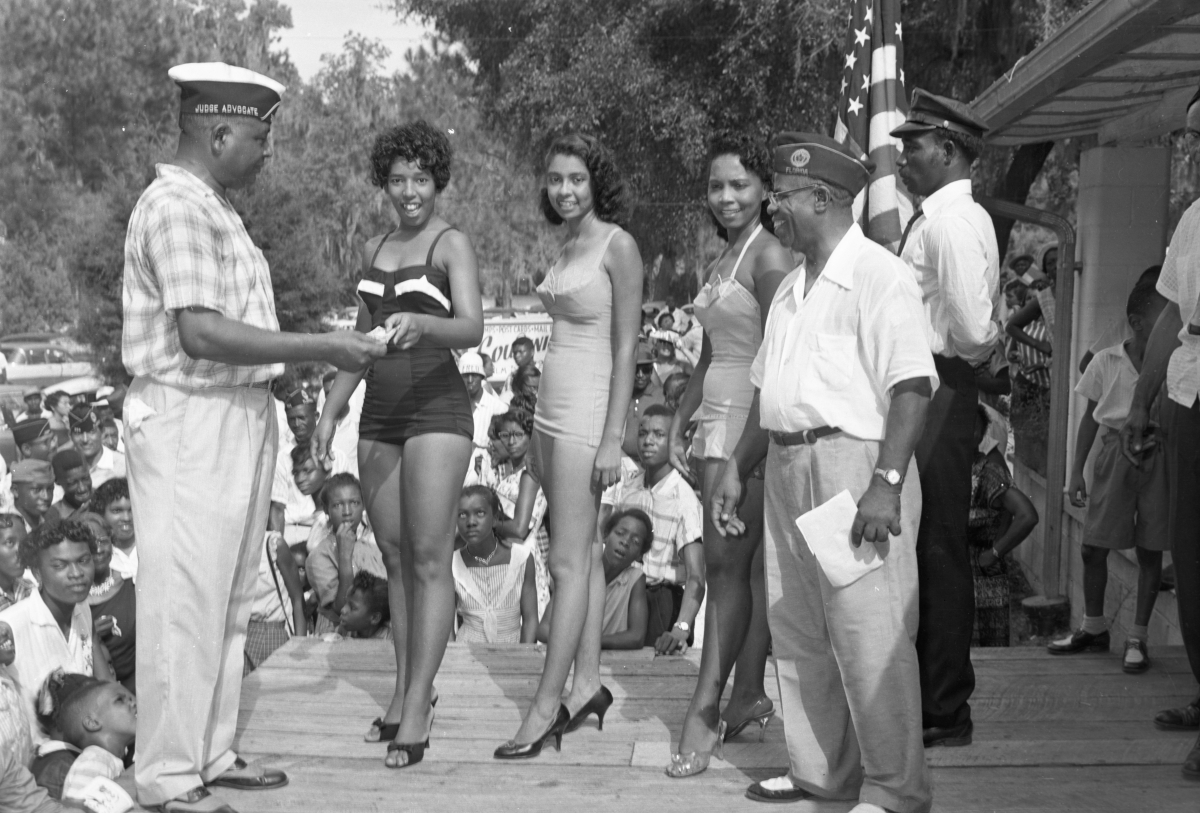

Finalists on stage in the 9th Annual Miss Paradise Park pageant.

For instance, a beach in South Carolina used a rope in the water as a physical dividing line, Vickers explained. Some found options in privately owned property, such as Frank Butler Beach on Anastasia Island near St. Augustine, which Butler established as a Black resort. American Beach in Jacksonville and Virginia Beach in South Florida were other spots that welcomed Black people.

While gathering research for her book, Vickers asked esteemed local journalist Bill Maxwell if he had ever gone to Paradise Park, and he’d told her he had and loved it.

Florida author Lu Vickers

Vickers recalled what he had said: “’It was really amazing that we, as Black people, had to find a place to sneak into the Atlantic Ocean!’ It was heartbreaking to hear him say that … so much coastline just forbidden to people; it’s just unbelievable.”

Paraphrasing what Vereen said in an interview decades ago concerning segregated accommodations throughout the country, Vickers said, “White people don’t realize basically how much money they’re leaving on the table by not opening the doors to African Americans.”

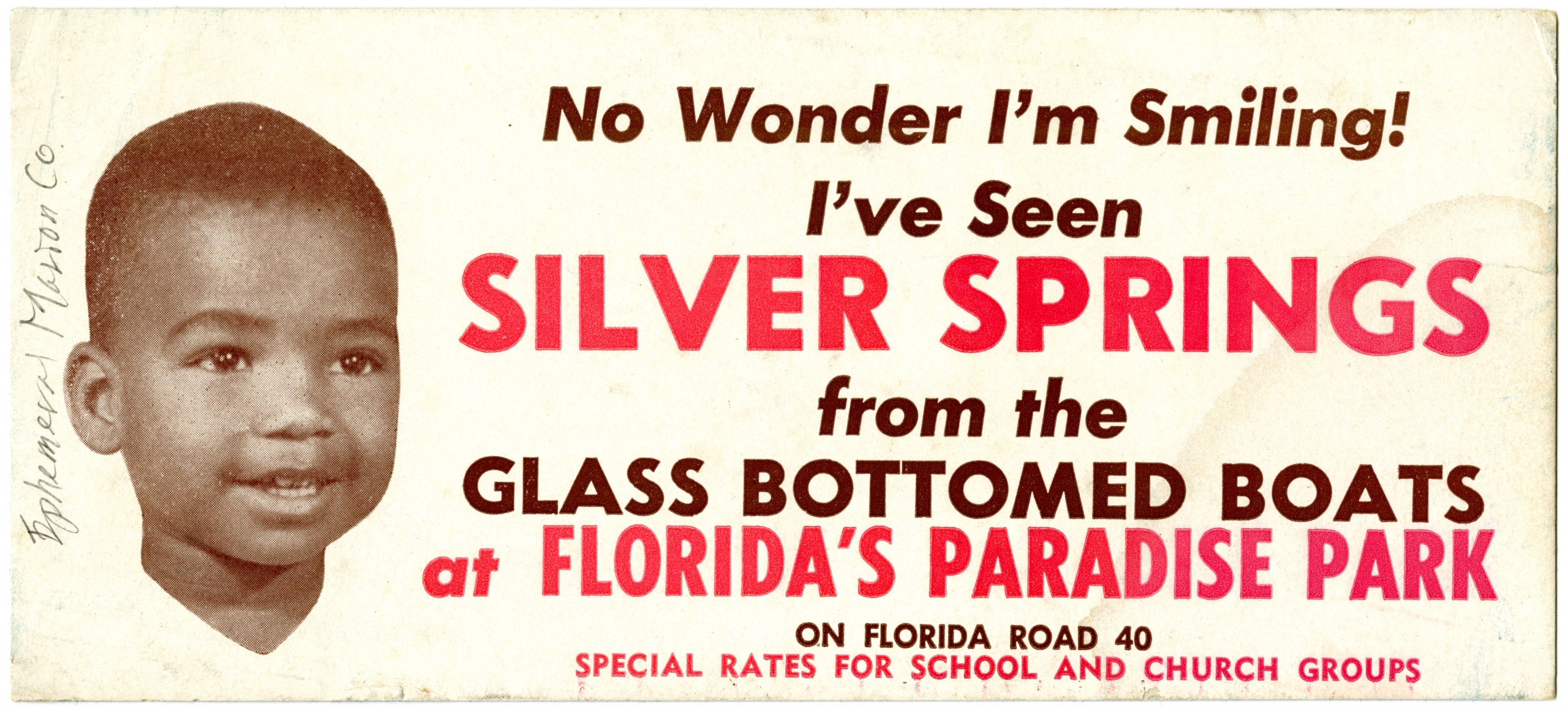

Silver Springs, near Ocala in Marion County, was founded in 1852, and expert Black captains piloted the Hubbard Hart line of steamboats on the Silver River for years, as they knew the area well. Its natural beauty drew visitors from around the country. It wasn’t until the 1920s that Ray and Davidson developed the land around the river into the attraction that became Silver Springs Nature Theme Park, with its famous glass-bottomed boats.

Though Davidson and Ray hired Black boat captains and Black visitors were permitted to walk into Silver Springs, they could not partake in any attractions, like boarding a boat for sightseeing tours — except on a designated “Negro Day,” once a year at specific parks.

As the captains were getting fed up with being unable to bring their families and friends on their boats or obtaining special permission to do so, they pushed for an alternative.

A basketball team from Illinois takes a ride on the glass bottom boat while visiting Paradise Park.

In response, Ray and Davidson opened Paradise Park about a mile downriver from Silver Springs. It featured the same glass-bottomed boats and other similar attractions such as a petting zoo, scenic jungle cruise, reptiles, softball field, a sandy beach and a dance pavilion.

However, in ways, the employees were still made to feel inferior, Vickers said, as Davidson often referred to his Black workers as “my niggers.” Often boats carrying white passengers would pass boats carrying Black passengers on the river. Vickers recalled interviewing one African-American woman who had gone to the park as a young child.

African-American men chatting in front of the Paradise Park sign circa 1950.

“She told me, ‘I didn’t know it was segregated. I thought we were just going with the people we liked!'” Vickers said. “She was a child; how was she going to know?”

The charismatic Vereen, a well-respected captain in the area, ran Paradise Park from 1949-1967.

“Eddie Vereen treated that place like his own personal paradise,” Vickers said, “and made sure that it was a very nice place for everybody to go to.”

He did act as a stern chaperone when necessary. Vickers explained that if he saw teenagers dancing too close to one another, he “would literally pull the plug on the jukebox!”

The park featured a popular beauty contest on Labor Day — Miss Paradise Park — sponsored by the local American Legion post and attracted girls from all over the state.

Ninth annual Miss Paradise Park pageant winner Carrie Johnson Parker-Warren receiving her prize.

“That was a huge draw,” Vickers explained. “People from all over, really the southeastern United States, would go there.”

There was even a snake handler at the park, and Vickers noted his response when someone had asked if he wasn’t afraid of snakes: “‘I’ve dealt with worse in human beings! I’m not afraid of snakes!’ He said, ‘They won’t come after you!'”

During the 1960s, the South became more and more desegregated, and by the decade’s end, Paradise Park was no more.

“They didn’t integrate it; they just closed it down,” Vickers said. “The community was really upset about that … a lot of people said, ‘Why don’t you just open it to everybody?’ But they closed it down, and at some point, somebody went down there and bulldozed all the buildings.”

Many African Americans visited Silver Springs in the ensuing years, but they felt it wasn’t the same, Vickers said, with one man explaining that he “felt like a stranger in my own home, and I didn’t go back.”

The laws may have changed, but many of the people’s attitudes didn’t, Vickers observed.

“It’s understandable to me,” she said, “because if you go, you’re still not treated well, and it’s not the same. They didn’t have the jukebox; you couldn’t bring picnics — there was a whole different vibe there.”

Paradise Park closed quietly in 1969, and the area is now covered by underbrush.

The “Remembering Paradise Park” lecture was a Florida Talks Event, a partnership between Florida Humanities and the Pinellas County African American History Museum.