About one in 13 Black or African-American children is born with the sickle cell trait and at least three million Americans, primarily Black, live with the trait.

BY YOLANDA GOODLOE COWART, Contributor

With the prevalence of sickle cell disease (SCD) and how it’s rampaging minority communities, it’s shocking how little attention is being given to it. The careless manner with which the disease is being handled is so extreme that the CDC doesn’t even know the exact number of people living with it in the U.S. The estimate is around 100,000 Americans.

Worse still, a survey of 1,042 practicing physicians, who were members of the Council of Academic Family Medicine organizations, showed only one in five were comfortable treating patients with SCD, and less than half were comfortable managing patients’ pain. Knowing the worrisome racial bias in the U.S. medical field concerning Black people and their threshold for pain, these statistics do not bode well for the thousands who suffer from SCD.

Sickle cell disease and its impact on the Black community

Discovered more than 115 years ago, evidence shows that SCD is an evolution of the human body to guard against malaria (another deadly disease found in countries along the equator). SCD is a disease where the red blood cells are sickle-shaped and stiff. These sickle-shaped cells are fragile and break up faster than the body can replace them, causing anemia in patients.

To have SCD, both parents must have the sickle cell trait. A person with the trait can be completely healthy and not have any problems associated with SCD at all. If both parents have the trait, each child has a 25 percent chance of contracting the disease. About one in 13 Black or African-American children is born with the trait and at least three million Americans, primarily Black, live with the trait.

Mary Murph, founder of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America St. Petersburg Chapter with the 2017-18 Sickle Cell Ambassador Antonesia Jackson at the 46th-anniversary sickle cell benefit on Sept. 22, 2018, at the St. Petersburg Country Club.

Persons living with SCD have crippling pain episodes or crises where many sickled cells damage and block blood vessels, making it difficult for blood to circulate normally. Usually set off by an infection, fatigue, unusual stress, over-exertion, or even high altitudes, a sickle cell pain episode or crisis causes severe pain and could require medical attention.

As one might imagine, the obstruction of blood vessels can damage different organs and lead to other health issues such as leg ulcers, strokes, and a higher risk of infection.

While SCD can affect people of any race or ethnicity, Black Americans make up more than 80 percent of those with the disease. In 2009, estimates showed that 8,374 to 14,236 African Americans were living with the disease in Florida, and 52 percent of those patients were women.

Equally concerning is the large number of people who have the sickle cell trait but are unaware of it. It is estimated that between 2.5 and 3 million people in the U.S. have the trait.

Healthcare inequities in Black communities

Racial biases in the healthcare system adversely affecting African Americans are not news. Many still remember the Tuskegee experiment, a 39-year ordeal that ended in the 1970s. More recently, stories like the ordeals Serena Williams and Dr. Susan Moore endured cannot be easily ignored or forgotten.

Williams, a world-famous tennis champion, requested a CT scan with contrast and IV heparin (a blood thinner) when she had trouble breathing after giving birth, but an ultrasound of her legs was done instead. The nurse, who Williams alerted about her symptoms, thought the pain medicine she was on was making her confused.

Dr. Susan Moore, a medical doctor herself who was being treated for Coronavirus, was told by the doctor in charge of her care that he did not feel “comfortable” giving her more narcotics. Despite Dr. Moore’s knowledge of complicated medical terminology and treatment protocols, she was made to feel like a drug addict in her sickness and hour of pain.

These experiences and many more have given the African-American community a healthy distrust of the medical profession. A poll conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and The Undefeated revealed that only six out of 10 Black adults trusted doctors to do what is right most of the time.

Twenty-one percent of the Black people polled indicated that they found it somewhat to very difficult to find a doctor that treats them with dignity and respect. Seventy percent felt that the health care system treats people unfairly based on their race or ethnic background.

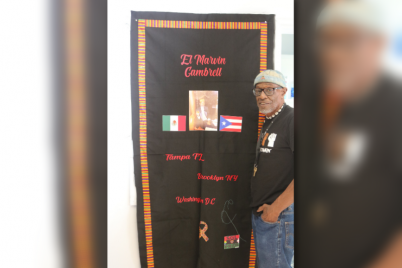

Each year, Mary Murph, founder of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America St. Petersburg Chapter, throws a Christmas party for sickle cell clients. Murph is pictured above with clients at Lake Vista Recreation Center on Dec. 4, 2021.

Imagine battling a blood disorder that is not as popular as hemophilia and cystic fibrosis and is prevalent amongst Black people and other minority groups. Think about the challenges you’ll face trying to get treatment for a pain episode or crisis that is characteristic of this disorder from a healthcare system that you don’t trust and that suspects people who look like you when they request pain medication. How would that impact your care?

If you guessed it would lead to medical practitioners suspecting you of being a drug addict, you’d be right. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines recommend that victims of SCD receive pain medication within 60 minutes of arrival at the emergency department.

Unfortunately, SCD patients experience longer wait times to see a doctor when they get to the emergency ward than other patients with chronic conditions due to prejudice, even though SCD patients suffer from higher degrees of pain and are a higher priority assignment in triage.

Another challenge is the predictably high healthcare cost of managing SCD. On average, it costs about $10,000 a year to treat children and around $30,000 to treat adults for SCD-related complications such as pain episodes/crises, organ damage, and strokes.

In 2019, the FDA approved two new treatments, the first in 20 years, for SCD — Adakveo (crizanlizumab) and Oxbryta (voxelotor). Both are lifetime medications that cost about $100,000 a year. This is almost double the U.S. median family income ($67,521 in 2020), where the median net worth for a Black household is about $24,000.

Well, what about health insurance, you might ask? That could help people afford the cost of this potentially life-saving treatment, right? Unfortunately, due to high unemployment rates (8.6 percent) in the Black community and low representation in jobs that provide health insurance for employees, 11.8 percent of Black Americans do not have access to health insurance.

What can be done to provide help for our community that is suffering these health challenges?

Sickle cell advocate fights against healthcare inequities

While there still needs to be a lot more done to fight against healthcare inequities in general and sickle cell disease in particular, some progress is already being made. U.S. Rep. and Florida gubernatorial candidate Charlie Crist and Mary Murph, president and founder of Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA), are at the forefront of the fight for increased funding and support for those battling SCD in Florida.

Crist filed a bill called The Sickle Cell Care Expansion Act to increase access to care for adults with sickle cell disease. The bill will put aside $200 million a year from 2023 to 2028, mainly as scholarships and loan forgiveness for hematologists (and those studying to become hematologists).

Almost 25 percent of the fund would be used as grants toward sickle cell education and advocacy. Backed by the Black Women’s Health Imperative and the American Society of Hematology, the bill has moved to House Committee on Energy and Commerce. Though the bill is yet to move from the House, Charlie Crist is optimistic that it will be passed before the end of his term.

Murph has been a sickle cell advocate for 50 years. Supporting her two daughters with SCD through more than 150 hospitalizations, five hip replacement surgeries, two gall bladder surgeries, and more, she has made her intimately aware of the challenges that face the African-American community trying to access treatment for this disease. Though she lost one of her daughters to the disease, Murph does not relent in her fight to propel research to find a cure.

Her challenging experience with SCD has allowed her to see firsthand how poorly local hospitals treat St. Petersburg SCD patients. She has also witnessed how inadequate patient care is for those suffering from SCD.

As a result, Murph has made it her mission to advocate for a Sickle Cell Unit in the newly planned expansion of the Moffitt Cancer Center in St. Petersburg.

If Congress passes The Sickle Cell Care Expansion Act, millions of dollars a year will be available to treat Sickle Cell patients. This funding could allow the Moffitt Cancer Center, which will sit between Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital and the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, to treat Sickle Cell patients better.

The proposed 75,000-square-foot medical building will be large enough to accommodate 8,000 patients a year. According to Moffitt Chief Operating Officer Sabi Singh, the center’s goal is to bring the best care closer to home. Including a Sickle Cell Unit will be doing just that for the many people battling SCD in the Tampa Bay area.

Many in the African-American community have long been managing the Sickle Cell Disease with little support and a lot of suspicions. These initiatives, The Sickle Cell Care Expansion Act and a Sickle Cell Unit at Moffitt Cancer Center in St. Petersburg, will help bring awareness to the disease, support hematologists, and provide better health care to patients.

Yolanda Goodloe Cowart is an author, small business advocate, civil rights activist, and human rights defender in St. Petersburg-Clearwater.