In 1951, Samuel Shepherd and Walter Irvin, part of the Groveland Four, were shot by Sheriff Willis McCall (standing) while they were being taken to a pretrial hearing. Shepherd died, and Irvin survived. The four young Black men were falsely accused of raping a white woman. Professor J. Michael Butler said Florida should be at the center of our understanding of the Civil Rights Movement. [State Archives of Florida]

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

CLEARWATER – The Pinellas County African American History Museum hosted author and lecturer J. Michael Butler, Ph.D., for a talk on the “Civil Rights Movement in Florida” on Nov. 3.

Butler debunked the outside perception that Florida is not part of the Deep South, that Florida is NASA, white sandy beaches, and, of course, Walt Disney World. The idea that Florida is better than or does not have the same race relations as George, Alabama, or Mississippi is a fallacy.

“Florida exceptionalism is the idea that somehow Florida is outside of what we consider to be American — particularly Deep South — race relations,” he explained. “Florida actually advertised itself to get tourists here as a place where ‘people knew their place.’”

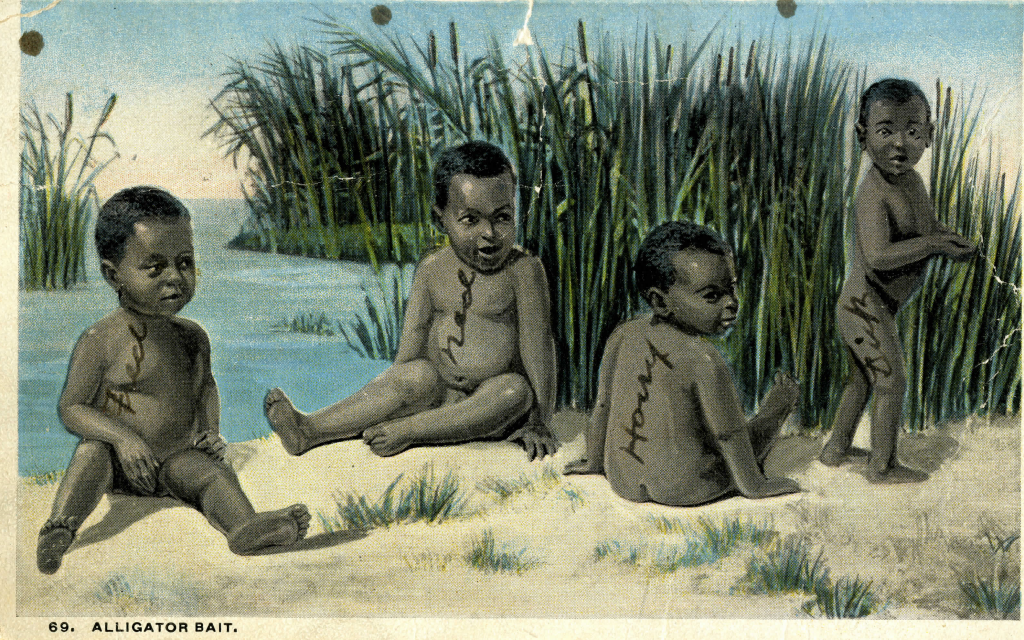

With vintage postcards sold to this day in some places in St. Augustine depicting scenes like alligators snapping at the seat of a Black man’s trousers or gators snapping at a Black man who has climbed a palm tree for cover, Florida is not exceptional in terms of our nation’s racist history, Butler said, but instead, it is hidden in plain sight.

Images such as these promoted white supremacy — the idea that no other race can reach white people in terms of intellectual, cultural, political or economic equality, he said.

“So, we see that white supremacy in Florida is deeply, deeply ingrained, even in the way that we manufacture our tourist trade,” he averred.

There are debates in some academic circles about whether Black children were used to feed alligators or if it was just on postcards. This undated postcard is thought to have been in circulation around 1918. [Public Domain]

Butler referred to the Ocoee Massacre of 1920 that occurred because Black people had the audacity to try and vote in the presidential election. In the town located outside of Orlando, 56 African Americans were killed by white renegades who went into the Black part of town and slaughtered indiscriminately.

“This is called a clearance when you try to drive out Black people with violence, claim land and businesses that don’t belong to you; that is a clearance.”

We also see that in 1923, with the Rosewood Massacre. White mobs destroyed a Black town in Levy County and killed residents on the unfounded allegation that a Black man had sexually assaulted a white woman.

“It was a false claim,” Butler stated. “That was a common practice throughout the South to precipitate these violent actions.”After five days of rioting, all Black residents fled Rosewood, and survivors would not go on record to talk about the slaughter until the 1980s. Rosewood was a clearance.

Florida’s new African American History standards state that if the Rosewood or Ocoee Massacres is taught in the classroom, educators have to teach that there was racial violence on both sides.

Claude Neal, in 1934, is considered to be the last spectacle lynching, which is when a person is accused of a crime and held while news of the lynching is advertised in advance, Butler explained. Neal was held for days while people came into the Marianna, Fla., to witness the sadistic torture and murder of a Black man.

“Some of the most horrific things I’ve ever read have been ritualistic lynchings of Black men in the American South,” he lamented. “They castrated the man and made him eat his own genitals.”

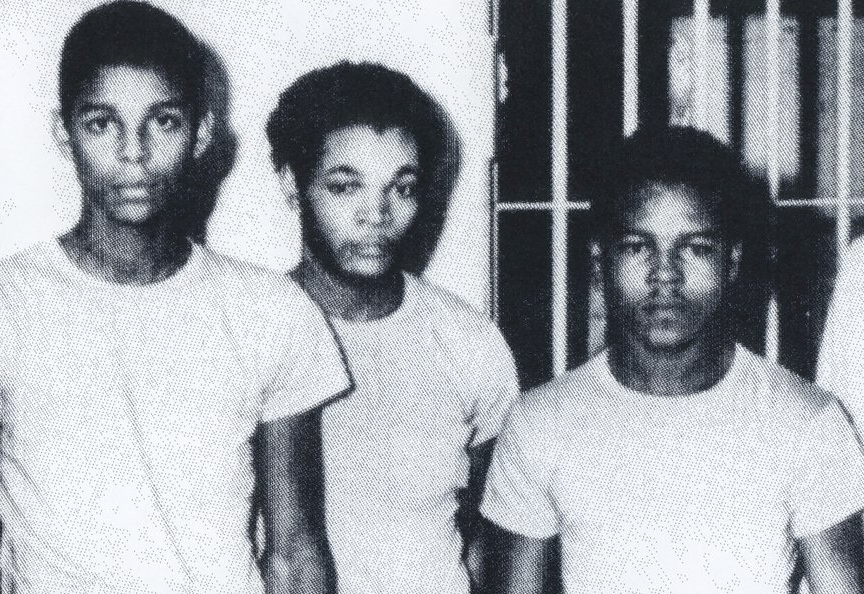

Four Black boys — the Groveland Four, as they came to be known — were accused of raping a white woman in 1949 in Lake County. One was killed trying to elude arrest while the survivors were beaten to coerce confessions, even though there was uncertainty on whether the woman in question was raped at all.

Left, Walter Irvin, Samuel Shepherd and Charles Greenlee. Ernest Thomas was killed eluding the sheriff. The three men were charged with raping a white woman in 1949. [ CC BY-SA 4.0]

The sit-in movement began in Greensboro, N.C., and spread across the South like wildfire. Butler said we hear triumphant stories of how, through economic pressure and outside attention, establishments integrated eventually.

“Not in Jacksonville,” Butler exclaimed.

Approximately 4,500 documented lynchings occurred in the U.S. from 1890 to 1920. Pictured above is Leander Shaw, who was lynched on July 29, 1908, in Pensacola, Fla., by an angry white mob. [Public Domain]

“If you want an example of the kinds of racial violence that have engulfed this nation at various times in its history, look no further than Florida. It has happened here,” Butler quipped.

Butler said lynching is an American scourge that we know too little about. We know that there were approximately 4,500 documented lynchings in the U.S. From 1890 to 1920 — the height of lynching in the country — Florida led the nation in per capita lynchings.

“It was more dangerous during that time to be a Black man living in Florida than living in the Mississippi Delta,” Butler asserted.

The urban-rural divide in different areas of the state can help you understand how various factors impacted the Civil Rights Movement, whether it’s tourism, industry, citrus groves or turpentine fields.

Butler gave the example of industrialist Henry Flagler, a key figure in the development of Florida’s Atlantic coast and founder of the Florida East Coast Railway. He said Flagler was a “perfect model of going to the state and renting convicts,” which is slavery by another name, to build his railroads.

“The urban-rural divide, convict lease, tourism, sit-ins, the space race, the federal presence that’s here with military bases — any question you have about the way that the Civil Rights Movement played out due to a variety of social and economic factors, you can find a place in Florida to study those phenomena,” Butler explained.

One of the reasons that Florida is not at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement is that it doesn’t have instances like Selma, Ala., he posits, referring to the infamous march in the Alabama city where Black protesters were attacked on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

There aren’t these flash points that make national headlines, Butler pointed out, and part of it is because of the state’s political approach to stonewall, delay and frustrate efforts to reach meaningful levels of integration.

After the Brown vs. Board of Education case, the Supreme Court decided that “separate but equal” in education was unconstitutional and that school districts were obligated to integrate. Yet, the person who came up with the strategy to delay it indefinitely, Butler said, was the attorney general of Florida at the time, Richard Ervin, Jr.

“A year after the Brown case, 1954, Florida attorney general crafted this philosophy that is adopted by the Supreme Court, and it can be summarized in four words: ‘with all deliberate speed,'” he said, referring to the vague language that allowed for states to proceed with integration at their own pace.

The state decreed that every county had to develop its own integration plan, so for “60-plus counties in Florida, you’re going to have 60-plus integration plans,” he said, adding, “it’s meant to delay.”

“Pinellas County’s approach was ‘we are going to delay integration by putting money into Black schools,’ Butler said, noting that their thinking was that Black parents would not want to integrate if their children had better resources. “And the fact that you build nine in fewer than a decade meant that ‘we’re pouring all these resources into Black schools because we don’t want Black kids in our white schools.'”

The Pupil Assignment Law of 1956 gave Florida county school boards the power to assign students to each individual school to get around integration legally.

“Florida is one of the first states that had public school integration. It occurred in 1959 at Orchard Villa Elementary School in Miami. Seven-year-old Gary Range and three other Black students broke barriers when they walked onto the grounds of the Liberty City school.

The two girls in this photo are Jan and Irene Glover, ages 9 and 7. Their mother, Irvena Prymus, walked them into Orchard Villa Elementary School in Miami on Sept. 8, 1959. [State Archives of Florida]

In the 1968 presidential election, 70.8 percent of Florida’s vote went to a combination of Richard Nixon, a candidate who captured white rage, and George Wallace, a staunch segregationist and white supremacist.

“We can’t get 70.8 percent of the people to agree on anything except that Richard Nixon and George Wallace were acceptable candidates for the presidency from Florida,” he laughed.

“If you want to know why the South went from Democrat to Republican, look at Florida. In 1968, you saw an overwhelming amount of the population go Republican for the first time in history.”

Butler said as long as there has been oppression, African Americans have been resisting it. Florida has no shortage of activists who risked their lives to stand for something bigger than themselves.

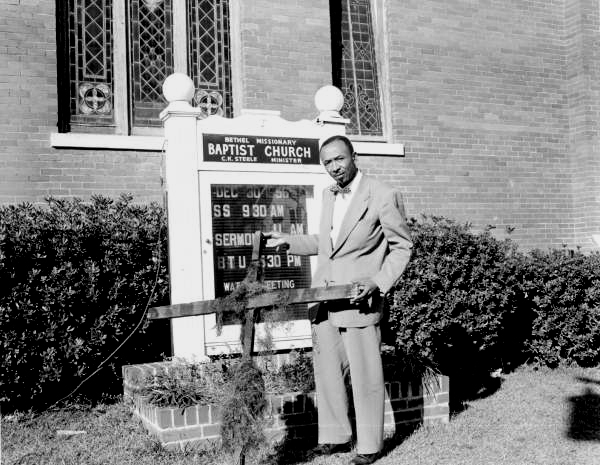

On Dec. 24, 1956, Rev. C. K. Steele (pictured) and Rev. H. McNeal Harris protested segregated seating on Tallahassee city buses by sitting in the middle instead of at the back of the bus. [State Archives of Florida]

Rev. H.K. Matthews, who, because of his civil rights activism, was set up and sent to state prison for a crime he did not commit.

Mary Mcleod Bethune, activist and educator, was a member of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet.” She became the first African-American woman to lead a federal agency in 1935.

Dr. Robert Hayling single-handedly organized the NAACP’s Youth Council in St. Augustine to participate in sit-ins and almost got lynched for his efforts.

The list of activists could go on and on. Florida has very few instances outside of St. Augustine where outside organizations were called in to help organize and help lead because Black Floridians did it themselves!

All the major national organizations are “represented at one place, at one time, in this state,” such as the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as countless homegrown civic organizations.

Dr. J. Michael Butler is the Kenan Distinguished Professor of History and Humanities Department Chai at Flagler College in St. Augustine. The “Civil Rights Movement in Florida” lecture was a Florida Talks Event, a partnership between Florida Humanities and the Pinellas County African American History Museum.