Southern Pinellas ‘Sundown Towns’ didn’t mean only Gulfport. In 1914, a sign posted by the Florida Beach Development Company warned people driving through present-day Kolb Park in Indian Rocks Beach that ‘Colored People Trespassing on This Property Will Be Prosecuted.’ Heritage Village | Indian Rocks Historical Museum

PINELLAS COUNTY — Last week’s article recounted a difficult chapter in Gulfport’s history. Informal and unwritten patterns of exclusion existed throughout much of the 20th century, creating what was known as a “sundown town.” Without passing a single ordinance, city leaders had conveyed a strong message to Black Americans: If you have business in Gulfport, get done with it before the sun sets.

Public comments by a Gulfport commissioner in May 1937 clearly communicated this mandate. Census numbers confirmed it. Black people represented only two of the town’s 1,581 residents in the 1940 census. A decade later, Black people counted as two of Gulfport’s 3,702 residents. No members of any other non-white racial group lived within Gulfport at these times when census takers canvassed the community.

Newcomers nearby

These trends continued as Gulfport’s population and municipal boundaries expanded. Five Black Americans lived within the municipal limits in 1960, but only three Black women – and no men – did at the time of the 1970 census, when the city had 9,976 residents.

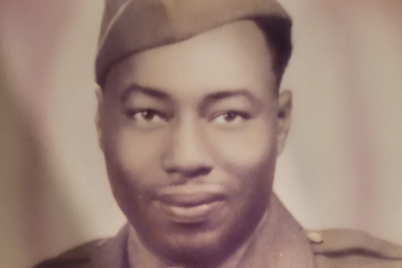

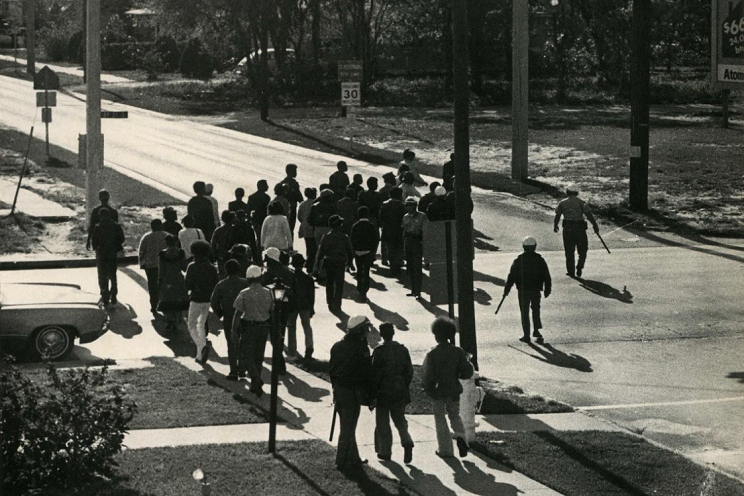

County deputies and Gulfport police officers escorting Black students removed from Boca Ciega High School across 49th Street S, at 11th Avenue, in mid-April 1973. | Pinellas Memory

Detailed, address-level census data is not yet available beyond the 1950 census. Whether these Black residents served as caretakers for white residents remains uncertain. What is certain, however, is that Black people did not call Gulfport “home.”

Gulfport residents during this period certainly took notice of population shifts to the east. During the 1940s, no Black people lived in Childs Park. Thirty years later, this subdivision started to transform to a majority of Black residents. Shared by two cities, a section of 49th Street South became a racial boundary.

In a January 2015 Creative Loafing article, current The Gabber owner and publisher Cathy Salustri Loper captured the memories of Louis Worthington, longtime Gulfport resident and spouse of Christine Brown, current vice mayor. In an interview, Worthington mentioned the presence of a sign warning Blacks not to “let the sun set on you in Gulfport.” Regardless of the exact wording or origin of any such sign, people in Gulfport paid attention to St. Petersburg’s neighborhoods immediately to the east.

A lesson in separation

While some Gulfport residents may have gossiped about “the other side” of 49th Street a half-century ago, evidence of this continued separation became a regular occurrence during schooldays along another road, 11th Avenue South.

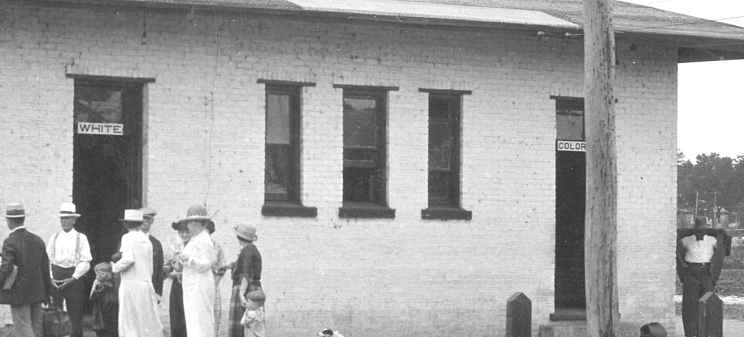

Legally, cities with Black populations required racial segregation. The railroad depot in Clearwater, shown here in 1922, had separate rooms for ‘white’ and ‘colored’ passengers. | Florida Memory

Beginning in the late 1960s, Black students who attended Disston Junior High School (now the Disston Academy for Progress and Enterprise) and Boca Ciega High School walked along 11th Avenue to and from their assigned campus, never alone, always in groups.

Tension gripped both of these schools, especially Bogie, during the late 1960s and early 1970s. When fights took place, Gulfport police and sheriff’s deputies separated groups. They sometimes marched Black students along 11th Avenue to the other side of 49th Street. During a particularly bad incident in April 1973, law enforcement stood at 49th Street, weapons in hand, escorting Black students to St. Petersburg’s side of 49th Street.

Pinellas sundown towns: Gulfport was not alone

Although Gulfport as it existed a half-century ago certainly met the criteria of a “sundown town,” its presence as the only Pinellas County community on the list of municipalities maintained by Tougaloo College tells an incomplete story. Other Pinellas municipalities also prohibited Black people from living in or staying there after sunset, or prohibiting their presence at any hour.

Members of Mount Olive Missionary Baptist Church in the Baskins-Dansville-Ridgecrest area south of Largo. The photo noted the location as ‘Indian Rocks, Fla.,’ a place where members would have faced immediate arrest if they swam at that time. | Heritage Village

These patterns of exclusion occurred throughout America, and well into the 20th century. In the years before the Civil War, legislators in California, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Oregon even passed laws to outlaw former slaves from entering these “sundown states.” Some of these laws persisted as troops from those states fought against the Confederacy during the Civil War. Oregon’s law remained on the books until 1926.

“Sundown suburbs” also appeared, often created as zones for those who left urban areas during periods of white flight. Levittown, located on Long Island and one of the best-known postwar American suburbs, enacted prohibitions during the 1950s that prevented non-whites from living in that New York community.

Noted folklorist and Jacksonville native Stetson Kennedy, a man who once infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan, wrote about this phenomenon throughout America when he published Jim Crow Guide: The Way It Was in 1959. Looking far beyond Florida’s boundaries, he devoted an entire chapter to “Who May Live Where.”

Sign of the times

Gulf beach settlements purposefully excluded Black people through the mid-20th century. In 1914, a sign posted at the Indian Rocks Beach City Park, now Kolb Park, clearly warned that “Colored people trespassing on this property will be prosecuted.” Occasionally, signs with more menacing warnings, posted by individuals rather than municipalities, appeared elsewhere along the coastline.

When Clearwater Mayor H.H. Baskin learned in July 1932 that some Black people had assembled along a remote area of Clearwater Beach to swim after nightfall, he issued a stern warning: “I am sure the Negroes of Clearwater will obey the dictates of public sentiment and cease going to the island at all.”

In May 1934, Klan members lit a 20-foot high cross with an 8-foot crosspiece on Clearwater Beach. Two separate cross burnings took place on an evening in May 1960. One burned along the causeway near Belleair Beach and the other along the approach to the Courtney Campbell Causeway, the swimming area for Clearwater’s Black residents at that time.

Unpacking Largo history

The citrus-packing industry centered in Largo a century ago required Black laborers. While Black people comprised much of the workforce that harvested crops on Largo-area groves and farms, patterns of racism and a municipal ordinance prevented Black people from living within nearly every square-inch of Largo.

Black workers, such as these men harvesting grapefruit in the Largo area in 1948, enriched the local economy even as they lived outside of the city. | Florida Memory

A July 12, 1907, article in the St. Petersburg Times (now Tampa Bay Times) entitled “Largo Looming Up” painted a picture of this emerging agricultural community. The reporter characterized Largo, a municipality that had incorporated two years earlier, as a place where “people are the most hospitable; and lived the best; and no blind pigs were allowed there; and no negroes; and no other nuisances.”

A measure of separation

At a time when unwritten threats against Black people were all that were needed for Largo to effectively be a “sundown town,” commissioners took the extra step of adding a measure in the town’s 1934 ordinances. William F. Belcher, two McMullens, John S. Taylor, and M.W. Ulmer – all town commissioners involved in the citrus industry – approved Section 339, an ordinance calling for the “Segregation of Races.”

After its passage, authorities could issue of fine of $50 or a 60-day jail sentence to any member of the “African or Negro race” caught living outside of the designated “Negro quarters” for “each and every day” they dwelled within prohibited town limits. The commissioners who profited from the labor of Black grove workers carved out an exception for “employees or servants of members of the white or Caucasian race.”

A dark legacy

At that time, most nearby Black workers lived in unincorporated settlements immediately south of Largo. Known today as the Baskins-Dansville-Ridgecrest area, Largo and county officials purposefully segregated these residents from encroaching white developments during the mid-20th century.

The residents of Baskins, Dansville, and Ridgecrest south of Largo lived separately from their neighbors to the north. | Pinellas Memory

The county planned to convert a widened area of McKay Creek known as Taylor Lake into a county park in the late 1950s. To prevent Black residents of the Baskins-Dansville-Ridgecrest area from climbing over a fence to access what is now known as John S. Taylor Park, they created a smaller park then known as “Ridgecrest Park for Negroes” where Ulmerton Road curves toward Walsingham Road.

As an added measure to quash demands for a Black bathing beach in mid Pinellas, during the spring of 1959 officials hired crews to dredge a section of McKay Creek within Ridgecrest Park to create a designated swimming area. Today, signs clearly warn anyone walking along this section of Ridgecrest Park of the ever-present danger of alligator attacks.

An expanded area of McKay Creek, created in 1959 as a bathing beach for Blacks in Ridgecrest Park, has always had many alligators swimming in it. | James Schnur

Sundown towns existed throughout America. The Gulfport of yesteryear is not the same city as today. Similarly, other areas that certainly would have qualified as “sundown towns” a half-century ago – locations including Pinellas Park and much of Lealman – no longer fit this description. Remembering these moments may be difficult, but these times of exclusion are part of our shared history.

This article was originally published in The Gabber on March 23, 2023.