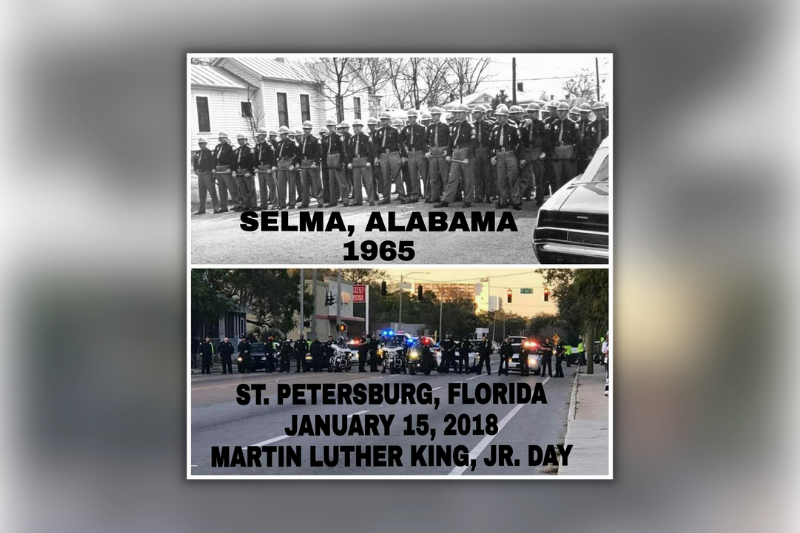

The City of St. Petersburg enacted 1960’s style policing to control the Black community after the Martin Luther King, Jr. Parade in 2018.

By J. S. Cooper, Contributor

ST. PETERSBURG — On July 8, the virtual Building Bridges and Supporting Racial Equity in St. Petersburg community conversation presented topics investigated in the Structural Racism Study by the University of South Florida and the City of St. Petersburg.

The study’s goal is to improve the quality of life for St. Pete’s Black community by examining how structural racism has impacted the systems that control and influence the city’s residents.

Reports that pre-dated the study include One Community’s Economic Status of Black St. Petersburg study and the Pinellas County Equity Profile by UNITE Pinellas. Both served as a foundation for the comprehensive study focusing on the current quality of life concerns and the historical impact of structural racism on St. Petersburg’s Black residents.

Dr. Ruthmae Sears, principal investigator on the Structural Racism Study by the University of South Florida and the City of St. Petersburg.

The research team chosen to lead this study includes Dr. Ruthmae Sears (principal investigator), Dr. Johannes Reichgelt (co-principal investigator), Dr. James McHale (co-principal investigator), African American Heritage Association’s Gwendolyn Reese (co-principal investigator), UNITE Pinellas’ Tim Dutton (co-principal investigator), One Community’s Gypsy Gallardo (co-principal investigator), Dr. Dana Thompson Dorsey (co-principal investigator), and Dr. Fenda Akiwumi (co-principal investigator).

When a preliminary report was issued in May, Sears shared, “This study seeks to describe historical trends in the community and consider how history has influenced the current initiatives of inequities that exist in housing, economics, wellbeing, educational outcomes, and the criminal legal system.”

The report shared insight into inequality and segregation issues dating back to the city’s first known Black settlers in the 1860s. It shone a light on six decades of ongoing subpar housing standards, redlining, and the continued struggle to equalize schooling and education for Blacks post-desegregation.

Study results concluded that Black residents earn less than their white counterparts at similar education levels, are more likely to die in childbirth, and deal with higher arrest and incarceration rates.

The community outreach portion was conducted by Jabaar Edmond, activist, filmmaker, and program director of Community Development and Training (CDAT), and USF student collaborators Jalessa Blackshear and Casey Lepak. The July town hall was another opportunity to gather insight from the community.

“Our goal is not to do just another report but to provide a practical and timely recommendation that could be enacted by the community, for the community,” said Sears, who serves as project administrator.

During the town hall, Sears led the conversation with a PowerPoint presentation that reviewed the study’s key terms, methods, and components. The four components of the study involve historical and current research, community conversations, a comprehensive report, and recommendations.

After Sears’s overview, attendees were split into five breakout rooms for 40 minutes to discuss their experiences with structural racism, criminal and legal systems, and recommendations for advancements.

When interviewed by phone, activist Jabaar Edmond stated that the events which transpired during the 2018 Martin Luther King Jr. Day Parade ultimately led to the formation of the study. On that day, the City of St. Pete and the police department blocked off every intersection in south St. Pete, functionally “caging” the residents and impeding their free flow of movement throughout the area during the day.

Officers also stood guard at several south St. Pete intersections and cracked down on vendors selling items along the parade route without a permit. St. Pete said the approach was meant to keep people safe but later apologized for the lack of communication.

This caused outrage and concern, with residents stating police officers took a “militant” approach to what should be a day of celebration. Videos circulated online after the parade showing officers confronting people, particularly over parking.

Edmond and others began meeting with city council members and the chief of police to advocate for the Black community. They started with community meetings at the Enoch Davis Center, where they formed the MLK committee. From that point on, the MLK committee came together with the St. Petersburg NAACP to further advocate for change.

“We went to the city council, and city council unanimously voted for a Sunshine Committee for African American Quality of Life,” shared Edmond.

However, that committee has still not been instituted. Instead, three and half years later, the structural racism study was born with the help of USF St. Petersburg and the City of St. Petersburg.

Although Edmond had a formal role in this study, he shared that, in reality, the community did not advocate for a structural racism study but racial equity. He expressed concern that the recommendations went into city hall one way and came out another way.

“We are not celebrating this,” he acknowledged. “No one is talking about this [study] but the people involved. This is not what the community asked for,” said Edmond.