BY RAVEN JOY SHONEL, Staff Writer

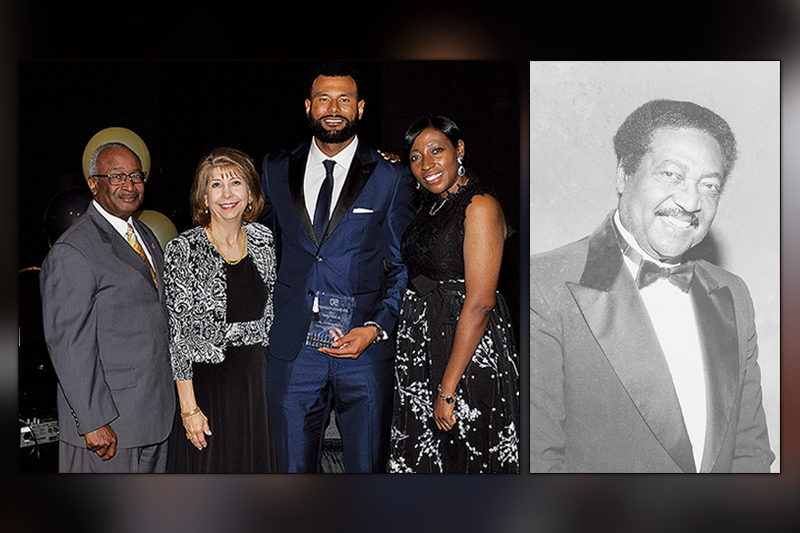

ST. PETERSBURG – Fifty years of local African-American life was celebrated last Friday night at The Weekly Challenger’s 50th anniversary. The community showed up and out for this momentous occasion in Pinellas County history and to honor the legacy of its founder, Cleveland Johnson, Jr.

“How many of you remember the first time that you saw your photo in The Weekly Challenger or your child’s,” asked Nikki Gaskin-Capehart, director of Urban Affairs, as she and Congressman Charlie Crist gave the welcome.

For Gaskin-Capehart, her first time in the Challenger was for winning an oratorical contest as a teen for the Elks Lodge. No doubt, she was one of the hundreds in the room who could recall their first time in the paper.

Emmy Award-winning broadcast journalist Trevor Pettiford served as Master of Ceremonies. He introduced videos from the incomparable actress Angela Bassett and actor and comedian Justin Hires, who fronted the television series Rush Hour and now stars in the hit series MacGyver. Both entertainers grew up in St. Pete and wanted to congratulate the Challenger for 50 years of serving the community.

Mayor Rick Kriseman was on hand to bring greetings from the City of St. Petersburg and a video presentation featuring community members speaking on the legacy and importance of preserving the Challenger was shown courtesy of the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg.

Once Rev. Dr. Wayne Thompson gave the invocation and blessed the food, dinner was served. However, this was no ordinary dinner. Not only was the audience treated to Floribbean soul food by Callaloo Catering, but they were also dazzled by the sounds of Cleo Heart, the Mt. Zion Progressive Main Sanctuary Choir and a spiritual dance performance by the Mt. Zion Progressive Pure Expressions Dance Ministry.

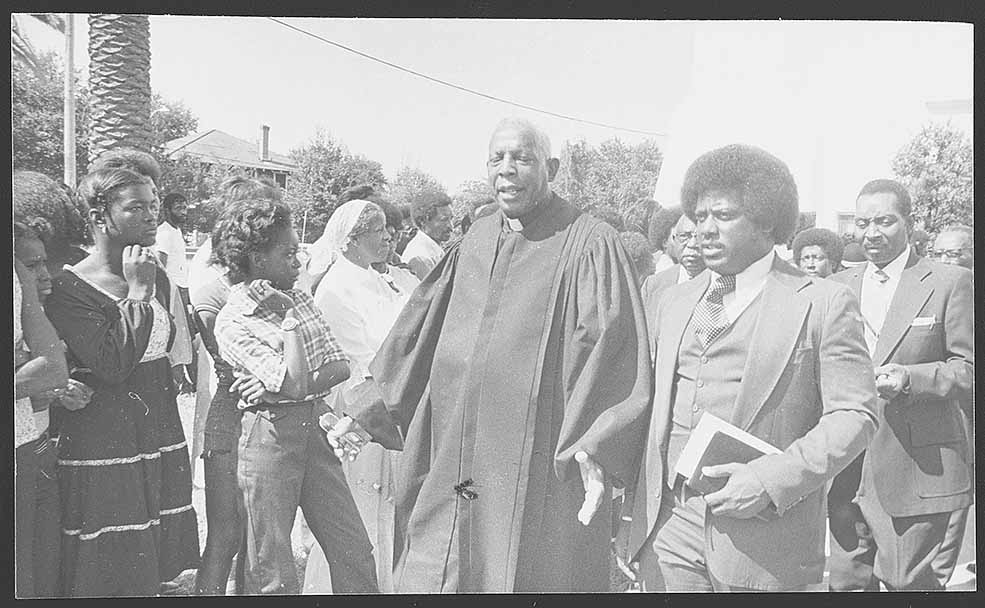

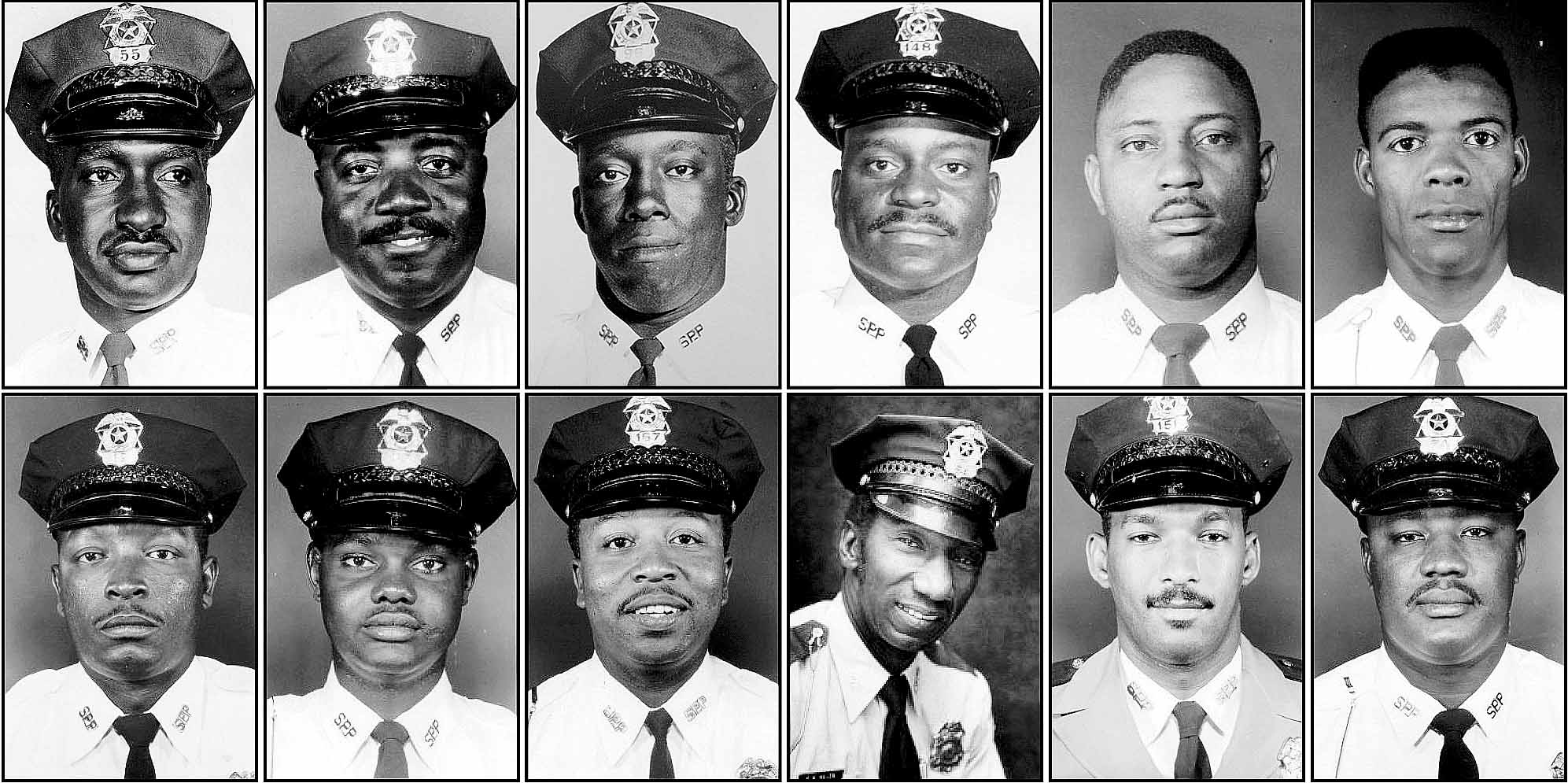

Instead of a keynote speaker, the planning committee decided to present, through a collage of pictures from the archives of The Weekly Challenger, a few of the community ancestors who played a major role in the shaping of the history of St. Petersburg. The segment was voiced by Senator Darryl Rouson, Gwen Reece, Daniel Sanders and Angelina Fletcher.

Titled “I AM,” this portion of the program was so popular that Reece, who researched and wrote the segment, has decided to do a weekly column highlighting local historical figures.