The area known as the Gas Plant neighborhood was the second African-American neighborhood formed in St. Petersburg between 1890-1900.

By Gwendolyn Reese

The area known as the Gas Plant neighborhood was the second African-American neighborhood formed in St. Petersburg between 1890-1900. Originally known as “Cooper’s Quarters,” the area was owned by Leon Cooper, a white business merchant.

It ran along Ninth Street South and south of First Avenue South. Like the earlier neighborhood of Pepper Town, formed between 1888-89 along Ninth Street between Third and Fourth Avenues South, Cooper’s Quarters was also settled by the influx of African Americans coming to the area to complete the Orange Belt Railway.

Along with Methodist Town and an area referred to as Goose Pond, these two neighborhoods were the only places Black people could call home in the city.

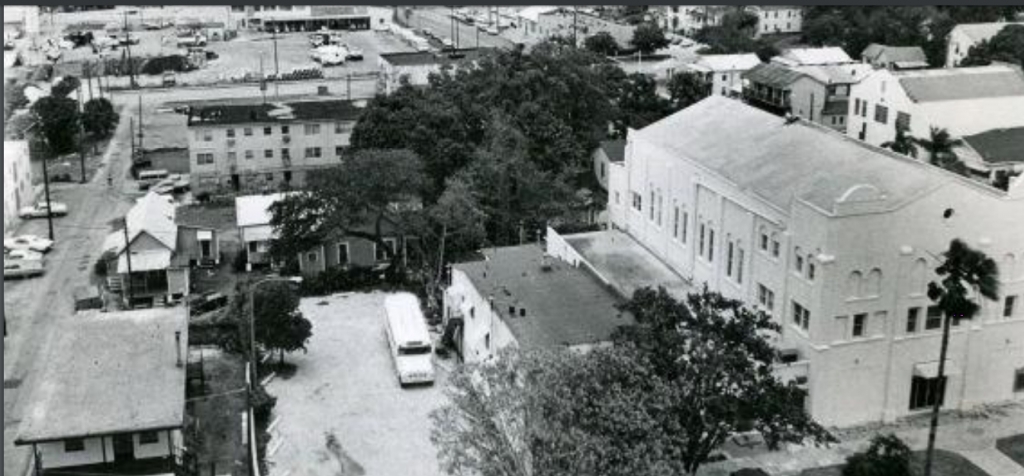

As the population of Cooper’s Quarters grew, the neighborhood expanded and became known as the Gas Plant neighborhood. This was because of the natural gas cylinders that dominated the skyline.

The neighborhood was home to many people, me included, who still have pleasant memories of growing up there. The communal fish fries on Friday, crab boils on Saturday and barbecues were a major part of the social life of the neighborhood, as was the sound of children’s laughter as they played kickball, hopscotch and four-square in the alleys and backyards of the homes along Sugar Hill, Dixie, and Dunmore Avenues.

Mango, avocado, guava, and other fruit trees abounded alongside sugarcane in the front and backyards of the homes in the neighborhood. I have particularly fond memories of the cherry bush hedges along one side of Dr. James and Fannie Ayer Ponder’s home on Fifth Avenue South, or Sugar Hill, as so many people remember it.

The Gas Plant neighborhood was a bustling community where many of us worked, lived, played, and died. It was the home of the first school for Black children, Davis Academy, later named Davis Elementary, which opened in 1910 and the private McCray’s school.

Bordered to the west by the gas tanks and to the east by Webb’s City, the Gas Plant neighborhood was home to a number of Black churches, businesses, and homes. Also, the Harlem Theater and the James Weldon Johnson Branch Library were a part of the Gas Plant neighborhood, and Campbell Park was in close proximity.

This vibrant, flourishing, mixed-income neighborhood was devastated first by the interstate and then completely gutted with the construction of the baseball stadium now known as Tropicana Field, or the “Trop.” But baseball was not what was originally promised to the residents of the neighborhood.

On Sept. 7, 1978, the city council passed a resolution declaring the neighborhood a redevelopment area and adopted a written proposal that included affordable housing and an industrial park that would create between 620 and 688 new jobs. According to an article in the St. Petersburg Times written by Theresa White on April 19, 1979, the plan was opposed by the Module 16 Advisory Committee and the International Ministerial Alliance (IMA) because it would displace more than 800 Black residents.

The NAACP, along with several churches and residents, had already voiced their opposition. The primary criticism of the plan was that it was designed without asking the people most affected for their opinions. Residents were not consulted until the plans had been drawn up.

According to the news article, in order for the city to keep its promise of developing an industrial park and affordable housing, it would have “to acquire 185 parcels of land; demolish 262 structures; relocate 27 small businesses, 45 owner-occupants, and 281 tenant households.”

Elder Clarence Welch of Prayer Tower Church of God in Christ said his church was prepared to fight to keep their newly renovated church from being demolished. Many voiced that they were afraid they couldn’t afford to live anywhere else. But the concerns went unheeded.

In Nov. 1982, the IMA held a press conference in which they endorsed the Gas Plant area as the future home for the proposed baseball stadium.

The wheels were put into motion, and the race was on between Tampa and St. Petersburg for which city would be the first to build a stadium and attract a Major League Baseball team to the Bay area. In March 1983, Mark Johnson, staff writer with the Times wrote: “the Pinellas Sports Authority selected the Gas Plant area in St. Petersburg as the site for its stadium and even held a symbolic ground-breaking ceremony.” This was before a franchise had been awarded.

In 1984, the two gas cylinders, which served as neighborhood landmarks for so many years, were dismantled. This was the beginning of the end for the Gas Plant neighborhood.

In July 1986, three years after the symbolic groundbreaking and eight years after the referendum of 1978, six of the nine city council members voted to build the stadium on the site without allowing it to go to referendum.

In 1986, City Manager Robert Obering supported the plan. Mayor Edward Cole, Jr. and Councilmembers Bill Griswold and Dean Staples voted against the stadium. Councilmembers Martha Maddux, J.W. Cate Jr., Robert Stewart, Chuck Fisher, David Welch, and Bill Bond Jr. voted to build the stadium.

In June 2008, Robert Stewart, a member of the council in 1986, was quoted in the Times saying, “He believed voters would not have approved the stadium in 1986 when the initial cost was $85 million. But he had no regrets about voting for it.”

In 1988, the city acquired Laurel Park, a low-income housing complex from the Housing Authority, to build a parking lot for the stadium. Once again, Black families were moved from their homes and dispersed throughout the community, many times losing the support systems and safety nets that were integral to the health and well-being of families.

In 1987 construction began. The stadium would be built but without a baseball team. It would be eight years before a baseball franchise was awarded to the city. Until then various events were held in what was originally the Florida Suncoast Dome, including music concerts, ice skating shows, home and garden shows, the St. Petersburg International Folk Fair, basketball’s NCAA Final Four in 1999, and any special event that would reduce the Dome’s deficit.

In 1993, the Tampa Bay Lightning hockey team agreed to play in the Dome for two years, and the name was changed to the ThunderDome. In 1996 the ThunderDome became Tropicana Field. About 400 events were held at the Dome from when it opened in March 1990 to when it reopened in January 1998.

In March 1998, 20 years after the city council passed a resolution declaring the Gas Plant neighborhood a redevelopment area and promised a plan that included affordable housing and an industrial park, the Devil Rays played their first official game at Tropicana Field. This was the symbolic conclusion of a 20-year project that tore apart the heart of St. Petersburg’s Black community.

And now, 23 years after the first game was played in the stadium in 1998; 34 years after construction began on the stadium in 1987; 35 years after six of the nine members of the council voted to build the stadium on the site without allowing it to go to referendum in 1986; 37 years after the two landmark gas cylinders were dismantled in 1984; 43 years after the city council passed a resolution in 1978 declaring the neighborhood a redevelopment area and promised, in writing, a plan that included affordable housing and an industrial park offering between 620 and 688 new jobs; and approximately 130 years after the neighborhood was formed, we find ourselves once again deciding on the fate of what once was the Gas Plant neighborhood.

Will the promises made in 1978 be fulfilled in 2021? Our involvement in the process will determine the outcome. Get involved. Make your voices heard because your voices matter.

I am currently writing a book about the Gas Plant neighborhood. If you would like to share your experiences of growing up there, of stories passed down in your family about the area, or memories you have, please email me at aahaspfl@gmail.com.

this is a great article. I found it after seeing st pete is proposing to build a new rays stadium mixed housing business project thing promising much of the same things they did all those years ago. super sad that history continues to repeat itself even now 2022.