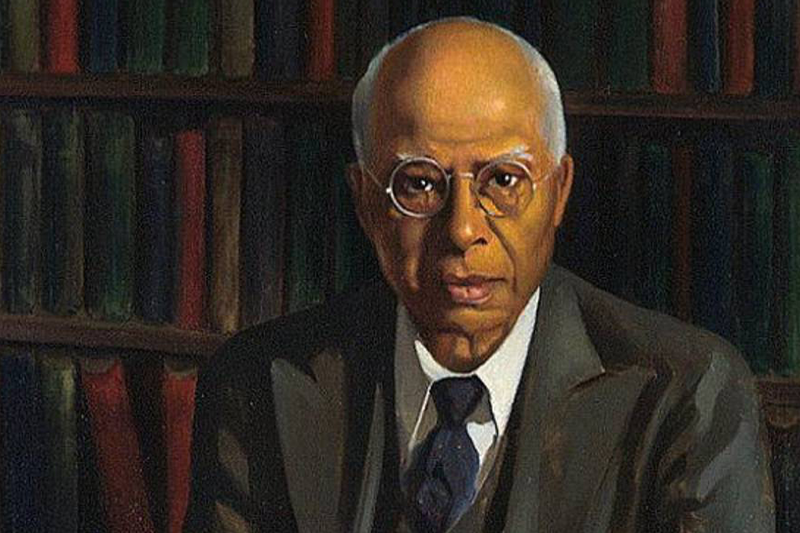

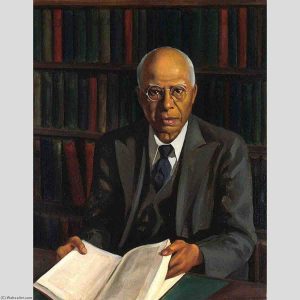

Monroe Nathan Work

By Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard, President, ASALH

It is incredible how historians determined the number of black people killed by lynching in America. A Nov. 2015 report by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Montgomery, Ala., found nearly 4,400 people were killed in lynchings in a dozen Southern states between 1877 and 1950.

The early researchers who combed newspapers, the black press, death records, and any information they could find, including eye-witness accounts, were unsung heroes. Without their work, much of the lynching history of black people would have been lost.

Monroe Nathan Work

A precious few recorded these evil events. One of the most prolific is someone most of us don’t know, but should. His name is Monroe Nathan Work, and he was an African-American sociologist who founded the Department of Records and Research at Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in 1908. He was the director of this extraordinary lynching archive until his retirement in 1938.

Work archived vital historical documentation that became the basis for many later reports that formed the statistical basis for collating the number of lynchings in America from Reconstruction throughout the Jim Crow era. Named “The Lynching Records” (1881-1953), it consists of 66 biannual reports.

Work also published “Negro Year Book, An Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro” and “A Bibliography of the Negro in Africa and America,” which contained 17,000 references to African Americans. Much of the information he investigated can be found at Tuskegee University’s National Center of Bioethics, Archives and Museums.

Work was born on Aug. 15, 1866, to Alexander and Eliza Work, who were born into slavery in Iredell County, N. C. When he was 23 years old, he graduated third in his class from an integrated high school in Arkansas City, Kan. He studied at the Chicago Theological Seminary after high school and then later at the University of Chicago where he received his bachelor’s degree in philosophy and a master’s degree in sociology and psychology in 1903.

Shortly after graduating, he joined W.E.B. Dubois’ Niagara Movement. In 1904, Work received and accepted an invitation by Booker T. Washington to come to the Tuskegee Institute where he began to establish his life’s work, which centered on recording and researching black life.

This provided the foundation for Tuskegee University’s Black History Archives. Work’s historical archives are so detailed and thoroughly researched that they are irreplaceable. Reading them is a joy for any serious student of black history.

In 1908, Work accepted a proposal by Washington to found the Department of Records and Research. While there, he began “The Negro Year Book,” a publication that incorporated, among other things, his periodic summation of lynching reports, which resulted in the Tuskegee Institute becoming one of the most quoted and authoritative sources on racial violence by lynching in America.

Lynching today is generally taken to mean a vicious mob killing of a black person or black people. Work’s research showed how frequently this brutal exercise of terror was used to frighten and control black people in the South. After 1886 in the South, nearly 80 percent of mob murders or lynchings were attacks against black men and women.

In Ishaan Tharoor’s Washington Post’s article entitled “U.S. owes black people reparations for a history of ‘racial terrorism,’ says U.N. panel,” he wrote: “Lynching was a form of racial terrorism that has contributed to a legacy of racial inequality that the United States must address. Thousands of people of African descent were killed in violent public acts of racial control and domination, and the perpetrators were never held accountable.”

The United States is still not held accountable, but black Americans will not forget. If not for the accounting of the numbers by Work and a few other people, much of this history would have been lost.

A new map project called Monroe Work Today is probably the most comprehensive map of proven lynchings from 1835 to 1964. Click here to view American terrorism at its best.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.