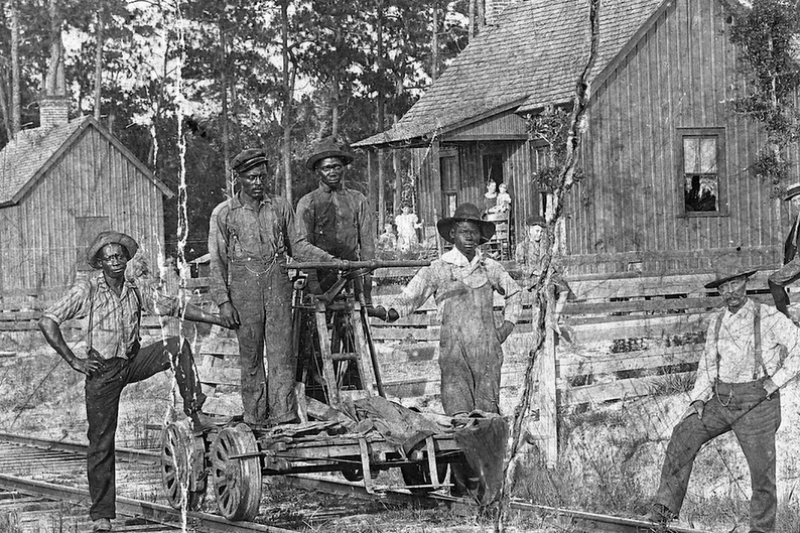

The Orange Belt Railway came to St. Petersburg in 1888. Black workers built the beds and laid the rails.

Gwendolyn Reese

The first African-American community in St. Pete was settled in 1888-1889 by black workers who helped to build the Orange Belt Railway. More than 100 blacks worked on the railroad, and their families joined many of them. They made their homes in an area located east of what is now Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Street and Third and Fourth Avenues South and named it Pepper Town.

Named because of the proliferation of peppers growing throughout the community, it established the first Masonic lodge, the Florida Grand Lodge, Prince Hall Affiliation, in St. Petersburg in 1893, a year before a white lodge was formed.

Black people were relegated to live in certain segregated neighborhoods tucked safely away from the tourists, white neighborhoods, and downtown. Shown here is Pepper Town, named for the proliferation of peppers growing throughout the community.

After the completion of the railroad, the workers and their families remained and found work as maids, day laborers, and some even found jobs in local hotels. As new settlers arrived, the second African-American community–initially called Cooper’s Quarters–was settled between 1890-1900.

Cooper’s Quarters, owned by white merchant Leon B. Cooper, consisted of wooden shacks and was located near Booker Creek, along Ninth Street, south of First Avenue South. Cooper’s Quarters later became known as the Gas Plant area. It was named for the two large cylinders housing the natural gas supply for the city.

There was a thriving business district in the Gas Plant area, and it was the home of Davis Academy, the first black school in St. Petersburg, as well as several significant churches.

In 1894, Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded at 912 Third Avenue North. A 1912 Polk City directory listed the location as Third Avenue North and Williams Court. The third African-American community of Methodist Town grew around and was named for the church.

It was on a side of town that was generally off-limits unless you were white. Black people were relegated to live in certain segregated neighborhoods safely away from the tourists, white neighborhoods, and downtown businesses. However, Methodist Town was just a “stone’s throw” away from all of that.

The third African-American community, Methodist Town, grew around Bethel AME Church and was named for the church.

Methodist Town and other African-American communities in the city consisted primarily of dirt roads and unpainted shacks owned by absentee white landlords who were often indifferent to the property and the people who rented it. But businesses still flourished. The Methodist Town Pioneers Reunion Committee reported that 68 businesses thrived in that community during the first half of the 20th century.

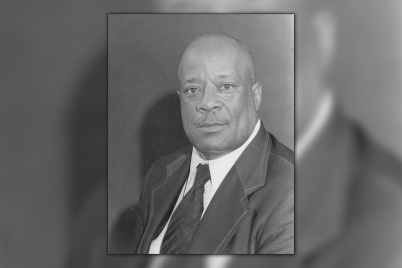

When redevelopment work began there in 1974, the city council changed the name from Methodist Town to Jamestown in honor of Chester James, Sr. Mr. James was a tireless worker, human rights leader, and community activist who at one time registered over 1,000 people to vote.

Goose Pond was another black enclave. It was in what was then a remote part of the city near Seventh Avenue and Thirty-seventh Street North. A few black families lived there until the 1950s. The draining of Goose Pond in the mid-1950s made way for Central Plaza, a shopping center in the area of 34th Street and Central Avenue with parking for nearly 2,000 cars.

In 1945, a report issued by the National Urban League cited poverty, overcrowding, and dilapidated housing as the norm in nearly every black community in the city. As deplorable as living conditions were for many in the black communities, these neighborhoods developed their own businesses, clubs, meeting places, dance halls, schools, and churches. Our communities were places of refuge, safety, laughter, kinship, communal values, culture, and dignity. We worked hard, played hard, laughed hard, and worshipped hard.

African Americans have always been essential to the development and the economy of this city. As stated by Ray Arsenault in his book, “St. Petersburg and the Florida Dream 1888-1950,” he wrote: “No amount of rhetoric could hide the fact that black labor was a crucial element of the local economy. Most of the women who washed the clothes and cleaned the houses and most of the men who carried the tourists’ bags, paved the streets, dug the sewer lines, collected the garbage, cleaned the fish, and constructed the city’s houses were black. Without the blood, sweat, and tears expended by people of color, St. Petersburg would not have been the up-and-coming city that local whites praised so loudly.”

Phase I of The African American Heritage Trail opened nearly five years ago in Oct. 2014. Earlier this month, the African American Heritage Association (AAHA) embarked on Phase II of the Heritage Trail, which will be in Methodist Town. When the small group of volunteers first began working on this project in July 2011, Dorthy Whitlock, a member of the committee, consistently and persistently cautioned us, “Don’t forget Methodist Town.”

After nearly eight years, we are keeping our promise to her and to the community that we will not forget Methodist Town. Beginning this month and throughout 2019, the AAHA will meet in Methodist Town, alternating between Bethel A.M.E. Church and the Dwight H. Jones Community Center. Meetings are held on the second Monday of the month.

If you grew up in Methodist Town, attended church there, and have fond memories, stories, pictures, and other memorabilia, please join us on Monday, March 11 at 5:30 p.m. at Bethel A.M.E. Church, 912 Third Ave. N in the Fellowship Hall.

Sources: The Olive B. McLin Community History Project, A Panoramic Glimpse of Black History by Ernest Ponder; St. Petersburg and the Florida Dream 1888-1950 by Ray Arsenault.

St. Petersburg’s Historic African American Neighborhoods, Rosalie Peck & Jon Wilson

An Ethnohistorical Analysis of the Political Economy of Ethnicity Among African Americans in St. Petersburg, Florida, Evelyn Newman Phillips