The Gas Plant neighborhood, circa 1970, where the redevelopment caused 285 buildings to be bulldozed; more than 500 households, nine churches had to be relocated and more than 30 businesses moved or closed.

BY RAVEN JOY SHONEL, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – The South St. Pete Democratic Club held a panel discussion last month that included providers of affordable housing, long-term residents of the area and city officials to gather information and ideas about the redevelopment of Tropicana Field in hopes to adopt and present policy proposals that may be incorporated into the plan.

Many in the community expressed concerns over the conceptual redevelopment plan of Tropicana Field during the Tropicana Master Plan – Scenario Two community meeting held Aug. 6.

“Nothing is set in stone yet,” said District 2 City Councilmember Brandi Gabbard. “This is all up for discussion, and it is all an open book at this point.”

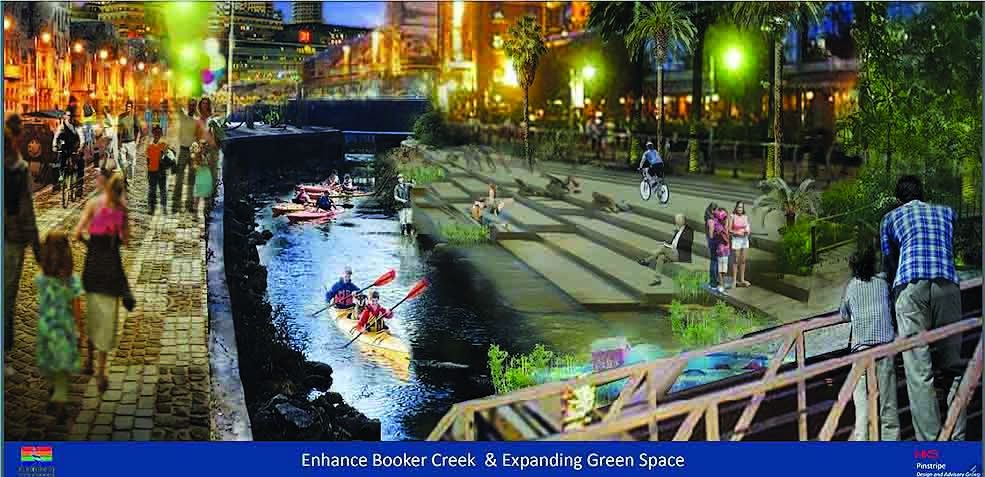

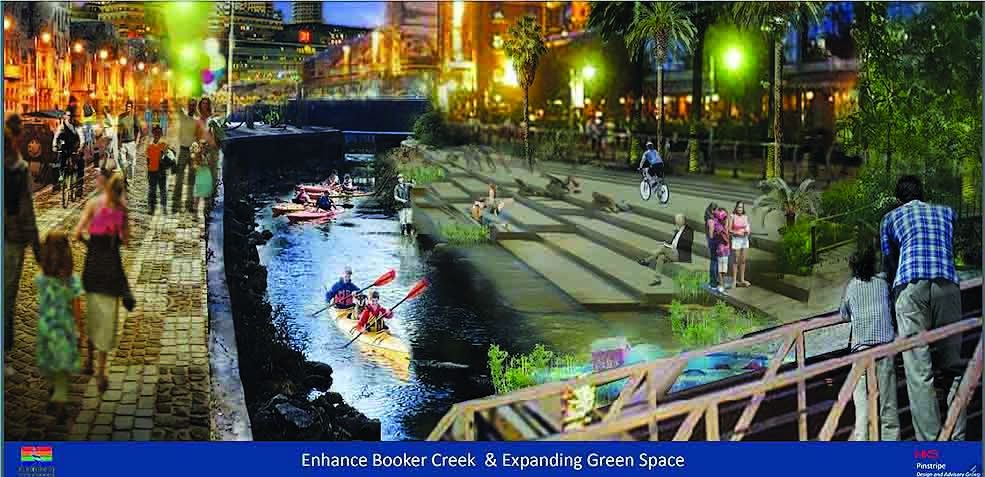

The Scenario Two plans showed retail space, an attractive promenade, entertainment space and even kayakers in Booker Creek. Gabbard called it “Hollywood,” and said the consultants hadn’t changed much from the first plan that featured the stadium.

“With a stadium has to come entertainment, has to come retail, has to come restaurants and something like a Riverwalk,” she stated. “I can assure you that myself, and I feel very confident in my colleagues on the council, will not be looking at turning this into Hollywood. We will be turning this into a community that can support us for generations to come.

L-R, Jack Humburg, executive vice president of housing at the Boley Centers, District 2 City Councilmember Brandi Gabbard and Mike Sutton, CEO of Pinellas Habitat for Humanity

Also on the panel sat Jack Humburg, executive vice president of housing at the Boley Centers, which offers community-based recovery services, rehabilitation, and housing in Pinellas County, and Mike Sutton, CEO of Pinellas Habitat for Humanity.

With the Oct. 1 date slated for the Scenario Two completion, Humburg said he’s sure that developers are “licking their lips” at the opportunity to redevelop the site with high-end housing carrying rents that exceed what most people can afford.

“If you go downtown and look at the development going on today, very little of that is affordable,” adding that Boley Centers provides affordable housing primarily focusing on the needs of individuals who have disabilities, mental illness, homeless and extremely low incomes.

He cited a 2015 United Way study conducted across the state of Florida called ALICE, or Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed, which is the definition of the working poor. Forty-one percent in Pinellas County fall into that bracket, which is about 165,000 people.

“They have jobs; they are above poverty level but can’t afford a place to live,” he said. “Add to that a disability or other barriers to housing, and you can imagine the difficulties we run into.”

He feels the best alternative for rental housing on the Tropicana site is finding an investor willing to use the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, which is matched dollar per dollar by the government and allows developers to be able to afford to build a property and rent at affordable prices. This program forces the developer to set limits on the amount of rent charged based on the individual’s income.

“It’s a complicated program, but I think it’s the best opportunity we have to be able to incorporate affordable rental housing into this development,” he said, noting that Boley is a partner in two of these kinds of developments. “We could probably put a couple 100 units in this area using the tax credit model.”

Gabbard said the city is setting up a dedicated funding source where they can control the money coming in and going out and will be able to hold the people utilizing the funds more accountable, making sure that they keep those properties affordable.

She’s also interested in not just economic development, but also community economic development.

“Sure we can say ‘let’s take all 85 acres and put housing on it,’ but if we’re not building jobs for people to be able to pay for that housing, what was the point?”

Gabbard wants a cross-spectrum of housing prices, which will, in turn, have a range of social-economic development, “so that the human nature can strive to always pull themselves up and do better,” she said. “We don’t want to see this turned into a luxury housing project; we also don’t want to see this turn into a low-income housing project.”

Gabbard’s sentiments harken back to an earlier time in St. Pete’s black community where the doctor or lawyer lived in the same neighborhood as the housekeepers or bus drivers, and all of their children played together.

Sutton said the city is in an affordable housing crisis. Since St. Pete is a tourist town, he averred, hotel and restaurant workers can’t afford to live where they work.

“That is a problem,” Sutton said.

Habitat’s goal is to build generational wealth through homeownership. Most people think Habitat for Humanity builds homes and give them away. However, they partner with the homeowner to purchase a house with a zero percent mortgage.

Since St. Pete is a peninsula, affordable housing space is limited due to the cost of land and the flood insurance needed to maintain the property. This leaves builders of affordable housing with very limited opportunities.

Sutton and Humburg do not envision the area being a place for single-family homes, but Trevor Mallory, a member of the Pinellas County Democratic Executive Committee, begs to differ.

“Like Mike said, he doesn’t think it’s an area for single-family homes, but I think you’ll be shocked to see how many single-family homes were there before the development of the Trop.”

The neighborhood that was bulldozed to make room for Tropicana Field in the 1980s was known as the Gas Plant neighborhood, named for the two imposing natural gas storage cylinders that towered over the area.

The Gas Plant redevelopment caused 285 buildings to be bulldozed; more than 500 households, nine churches had to be relocated and more than 30 businesses moved or closed.

One such church was First Institutional Baptist Church, which was built out of seashells. Davis Elementary School, the first black primary school in St. Pete made its home there, and the city’s first black physician, Dr. James Ponder, raised his family in the Gas Plant district.

There were shot-gun houses and neatly kept bungalows all lining the hand-laid Augusta brick streets. Renters and homeowners alike made up the neighborhood. This was old St. Pete—Jim Crow and all.

In the book “St. Petersburg’s Historic African American Neighborhoods” by Rosalie Peck and Jon Wilson, it recounts the variety of residents that called the area home.

“Tenements and shacks disappeared, but so did the fine homes in places like Sugar Hill, where the elegant Ponder home and its beloved cherry hedges disappeared, as did a score of other well-appointed houses. Even people who lived in less pleasant circumstances felt the still of displacement—what some call a slum or a shack may be no less a home and a roof overhead to a family, a grandmother or single mother.”

Along with the construction of I-275 and the displacement it created, probably no other project caused the degree of resentment than the razing of the Gas Plant neighborhood. The original plan to rehabilitate the Gas Plant neighborhood called for affordable new housing, an industrial park, and hundreds of new jobs, but what residents received was a baseball stadium, no jobs and displacement.

Lifelong resident Beth Connors said she wants some type of mandatory regulation to make developers put in affordable housing.

“You have to somehow push developers to put in affordable housing. We have been cut off at the knees,” adding that she would also like to see some type of commemoration to the community that was sacrificed in the name of progress.

South St. Pete Democratic Club treasurer Norm Scott wants to see small businesses be able to own and not lease. He spent years in banking, and leasing space was the highest expense on their ledgers.

“If we are not going to allow these small businesses to own their spaces to build equity that they can pass onto future generations, lease payments after a while will kill those small businesses,” he said, pointing to the small businesses who are no longer on Central Avenue because building owners priced them out of the market.

“We as a community will not build equity and transfer wealth to our descendants,” he said, demanding “not only affordable housing but also affordable price small business space.”

Gabbard said nothing is decided on yet, and that she would take the room’s concerns back to city council.

Post Views:

5,743