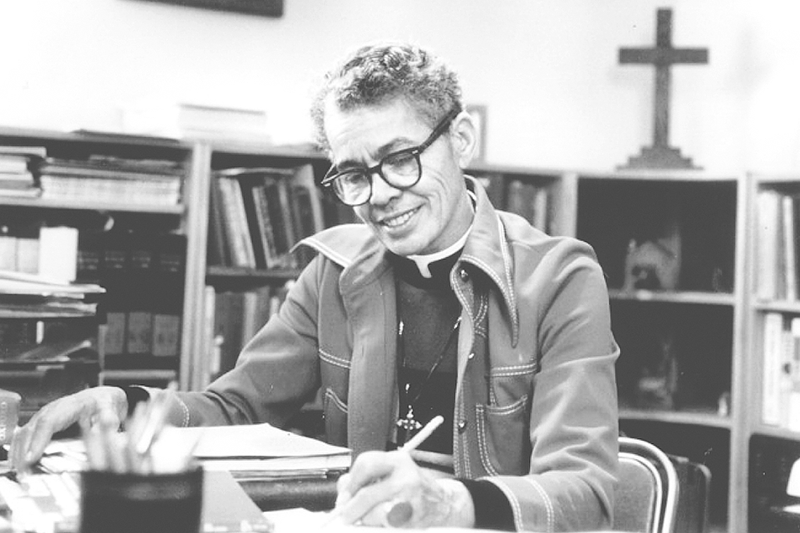

Anna Pauline ‘Pauli’ Murray’s work influenced the civil rights movement and expanded legal protection for gender equality. [Photo: Carolina Digital Library and Archives]

BY KEISHA BELL | Visionary Brief

What if you were denied access to an opportunity solely because of a characteristic outside your control? You did not choose it. You cannot change it. You may even embrace it, yet it creates unfair challenges at times.

Sometimes, these obstacles are easy to spot. Maybe you want to be a famous singer but are tone-deaf. Other times, the barriers are covert.

Meet Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray – an attorney, activist and author. Born Nov. 20, 1910, and died July 1, 1985, Murray made history by becoming California’s first black deputy attorney general in 1946.

In 1965, she made history again by becoming the first African American to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree (J.S.D.) from Yale Law School. In 1977, she made history again by becoming the first black woman ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Murray wanted to attend Columbia University, but because the school did not admit women, she was turned away. Instead, she attended Hunter College, where she graduated in 1933.

As a result of the laws in North Carolina in 1938, when Murray applied to attend the University of North Carolina, she was denied again, but this time it was because of her race.

In 1940, Murray was arrested for violating Virginia’s segregation laws when she sat in a whites-only section on a bus. By 1941, she was enrolled at Howard University School of Law. She was the only woman in her class.

Reportedly, on her first day of school, one of her law professors remarked that he did not know why women went to law school. Murray coined the term “Jane Crow” (hinting at “Jim Crow”), which was her way of drawing attention to how racial segregation adversely affected African-American women in particular.

Murray was elected chief justice of the Howard Court of Peers, which was the highest student position at Howard University. Turning heads, in 1944, Murray graduated first in her law class. Before Murray, the men who graduated first in the class were awarded the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, which allowed them to do graduate work at Harvard University. Murray was denied this opportunity, however, because she was a woman.

Reported, in response to this rejection, Murray wrote:

“I would gladly change my sex to meet your requirements, but since the way to such change has not been revealed to me, I have no recourse but to appeal to you to change your minds.”

At that time, minds were not changed. Murray earned a master’s degree in law at the University of California, Berkley.

Murray was increasingly frustrated by the disparity between the major part that black women play in the fight for civil rights versus how her leadership roles in the national policy-making decisions fail in comparison. In 1966, Murray co-founded the National Organization for Women (NOW). Supposedly, she thought it would act similarly to the NAACP but for women.

Before retiring from the practice of law, Murray was co-counsel and successfully argued the case of White vs. Crook. The ruling, in this case, is that women have an equal right to serve on juries.

Murray’s written work is just as impactful as her verbal advocacy of both civil rights and the rights of women. Her legacy is further recognized in that the National Trust for Historic Preservation named her childhood home a National Treasure, her family home was named a National Historic Landmark, and Yale University named one of its residential colleges, Pauli Murray College.

Because of her race and gender, many doors were closed for Murray. Many could not imagine someone who looked like her in certain environments or obtaining certain opportunities. Some flatly informed her that she was not welcome.

Keisha Bell