The lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, Ind., 1930

BY JACQUELINE HUBBARD, ESQ., ASALH President

There is probably no subject more terrifying to African Americans than the sordid, hateful legacy of lynching as a tool to control black dissent and support the institutionalism of racism in America. This violent history needs to be acknowledged by all Americans before its deep and severe wounds can be healed, and racial reconciliation can occur in this country.

It is, indeed, difficult to look at or think about, but look at and think about it we must. The violent enforcement of racial segregation haunts us to this day.

Historians agree that the lynching of black people was a direct reaction to Reconstruction with its concomitant enforcement of black voting and the Confederate loss of the Civil War. Jim Crow was enforced by it.

According to “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror” by the Equal Justice Initiative, the notion of a campaign of terror, including lynching, against black people started with the institution of the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan was born in Pulaski, Tenn., in late 1865 shortly after the Civil War with six Confederate veterans. In fact, Confederate General Nathan Bedford was the first Grand Wizard.

Lynching quickly spread throughout the former slaveholding states in the South and parts of the Midwest.

“The legal instruments that led to the formal end of race-based chattel slavery in America did nothing to address the myth of racial hierarchy…nor did they establish a national commitment to…racial equality,” the report states.

In 12 Southern states between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 to 1950, there are 4,084 documented racial terror lynchings, and more than 300 more occurred in other states during the same time period.

The Equal Justice Initiative reports that Mississippi, Florida, Arkansas and Louisiana had the highest rates of lynching, while Mississippi, Georgia and Louisiana had the highest number of lynchings.

Most people mistakenly think of lynching as mob punishment for the commission of a crime; on the contrary, lynching was an extra-judicial infliction of brutality, torture, burnings, dismemberment and killing of black people, often as a public spectacle without resort to due process or a trial.

Women were not excluded from these heinous crimes; as with black men, they were lynched for merely being accused of a crime or committing some social infraction against white people.

Black people were also lynched when the alleged perpetrator could not be found, but others were available. Frequent accusations were of alleged sexual assault against white women, being disrespectful, refusing to step off the sidewalk, arguing with a white man or trying to vote.

Sometimes lynching mobs targeted entire black communities such as in Tulsa, Okla., Rosewood, Fla. and in St. Louis. Even non-black persons were lynched, but almost all mob lynchings in the South were of black men and women.

Besides tremendous work by numerous anti-lynching individuals, such as Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. Dubois, Walter White and Charles Hamilton Huston, the most effective organization opposed to lynching was the NAACP. One of its most famous lawyers, Thurgood Marshall, after each lynching, would hang a sign out of the window of the NAACP’s New York office with the words: “A man was lynched yesterday.”

The horrendous practice of lynching African Americans only came to an end after successes during the Civil Rights Movement in the late 1950s, previous mass migrations of black people to the North and when other anti-lynching groups became more vocal.

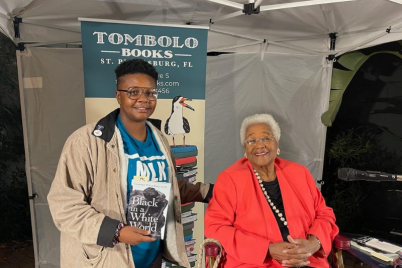

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.