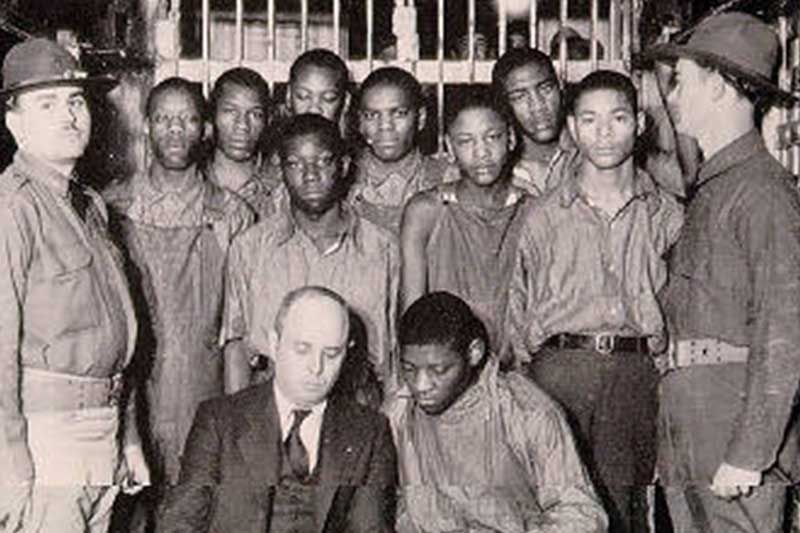

The Scottsboro Boys, with attorney Samuel Leibowitz, under guard by the state militia, 1932

BY KEISHA BELL | Visionary Brief

What if your son is arrested but is innocent of the crime he is charged with — a crime that carries death as its penalty — what would you do?

How would you control your emotions when the “evidence” against him is shaky, and witnesses are willing to testify on his behalf, but very few in the courtroom seem to care?

The court of public opinion may provide you with some comfort because it sides with your child, yet you know it is no match for the pressure of social norms that boil within the jury box.

Would you fundraise to finance a legal defense dream team?

Would you remember how God sent an angel to free Peter from prison and pray without ceasing, believing that that same God would send a miracle to your son to free him as well?

Meet Viola Montgomery. She is the mother of Olen Montgomery, one of the nine African- American teenagers falsely accused in 1931 of raping two white American women on a train in Alabama.

The nine who were arrested are more commonly known as the “Scottsboro Boys.” Olen was 17 years old at the time of his arrest. He was nearly blind.

Three of the Scottsboro Boys were tried before Olen.

Guilty!

Guilty!

Guilty!

Olen’s verdict was no different.

On April 9, 1931, Olen and seven other defendants were sentenced to death by electric chair. On April 28, 1932, Montgomery wrote a gut-wrenching letter to then-Alabama Governor Benjamin M. Miller in which she begged that her son be granted a retrial. She wrote the following:

“I love my sun [sic] just like your mother love you… so I will ask you plese [sic] have mursey [sic] on our Boys, said Montgomery in a letter to Governor Miller in Montgomery, Ala.

Despite getting no help from the governor of Alabama, Montgomery’s fight to save her son’s life continued. On May 13, 1934, she, along with Mamie Williams Wilcox (the mother of Eugene Williams), Janie Patterson (the mother of Haywood Patterson), Ida Norris (the mother of Clarence Norris), and Ruby Bates (one of the white accusers who admitted that she had lied about being raped), spoke at churches and at the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA in Washington, DC.

Although Josephine Powell, mother of Ozie Powell, became ill and was unable to speak, the mothers spoke to hundreds that day. Reportedly, Montgomery told the crowd at the YWCA, “If a colored woman had been attacked by white men, nothing would have been done.”

One could only imagine that the basis of Montgomery’s observation was a historical one. She understood how racial and gender intersections played itself out, particularly in the South, yet she refused to let it continue without lending her voice to raise awareness of these happenings. After all, her son’s life was at stake.

On July 24, 1937, the State of Alabama dropped all charges against Olen. Then-Prosecutor Thomas Lawson said that after “careful consideration,” every prosecutor was “convinced” that Olen was “not guilty.”

Keisha Bell

Montgomery’s son was finally free. Her perseverance exampled what was needed to right what many knew, even at that time, was wrong. The cases of the Scottsboro Boys established landmark legal cases. The power of a mother’s love spoke hope to a seemingly hopeless situation, encouragement to a child who was sidelined by societal discouragement, and life to her own weakening spirit. Her love is tenacious.

Keisha Bell is an attorney, author and public servant.