The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg and the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, Inc. (AAHA) produced the documentary “A Visual History of Civil Rights & Social Change in Pinellas County,” which delves into the history of the Black community in Pinellas County. Pictured above are students from Davis Academy, the first Black school in St Petersburg, which was located in the Gas Plant area.

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg and the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, Inc. (AAHA) presented the enlightening documentary “A Visual History of Civil Rights & Social Change in Pinellas County,” which delves into such topics as the history of the first Black settlers, establishment of Black neighborhoods and businesses, segregation, integration and voting rights.

Narrated in part by Gwendolyn Reese, president of the AAHA, the documentary serves as an entry point for education understanding and further exploration. The stories of how our community came to be are vital because they continue to shape who we are today. Without knowledge of where we’ve been, it’s challenging to move forward in a way that prioritizes equity for all.

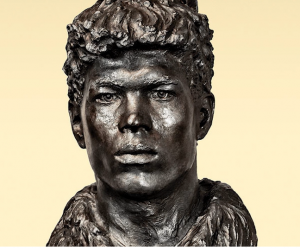

Estevanico, ‘Little Steven,’ an enslaved man from Morocco, is believed to be the first Black person on the continent.

The roots of inequity in Pinellas County started as early as 1528 when Panfilo de Narvaez landed on the shores of Boca Ciega Bay. Spain was exploring the “New World” looking for gold, and Narvaez and his men claimed the lands and the people they encountered for their king and church.

With them was Estevanico, “Little Steven,” an enslaved man from Morocco believed to be the first Black person on the continent. Narvaez explored Florida along the Gulf Coast and Texas and eventually traveled to Northern Mexico to meet up with the rest of his expedition. He and his men pillaged storehouses and exposed the indigenous Tocobaga people to disease.

The Tocobaga tribe primarily inhabited west Central Florida around the northern end of Old Tampa Bay and into Pinellas County, Reese explained in the documentary. Their culture blended indigenous cultures from Florida, Georgia, and Alabama. It is believed that their principal town was in Safety Harbor, and due to disease and raids, by 1709, the Tocobaga tribe was all but destroyed.

Around 100 years later, the Seminole people fled to Florida after a disastrous war against white settlers led by General Andrew Jackson. As the United States expanded and Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, the government forced many Seminoles to relocate to Oklahoma.

Today, the Seminoles remaining in Florida call themselves “the unconquered people” and are descendants of the roughly 300 people who avoided capture by the U.S. Army. Currently, more than 2,000 native people live on six reservations in the state and have established themselves in such industries as tourism, citrus, and cattle.

Building everything but wealth

The Orange Belt Railway came to St. Petersburg in 1888, and Black workers built the beds and laid the rails. Some stayed to settle the city’s first Black neighborhoods, while white people rode the railway and brought the first wave of the growing resort town’s tourist trade. Black labor was critical to the development of the city. Black laborers constructed the Orange Belt Railway, paved the streets, filled the sidewalks, dug the sewer line, and helped build some of the structures still in existence today.

“The first Black settlers on the lower Pinellas peninsula were John Donaldson and Anna Jermaine. Donaldson, a formerly enslaved person, and Jermaine, who would become his wife and the mother of his 11 children, came to the area in 1868 in the employment of Louis Bell, Jr., a white homesteader,” Reese said. “The Donaldsons purchased 40 acres of land near what is now known as Lake Maggiore. Donaldson worked as a truck farmer, among other things, to support his family, and he served as a community mail carrier.”

Ed Donaldson, the son of John Donaldson and Anna Jermaine Donaldson, was noted as the oldest living native-born resident of St. Petersburg and as Pinellas’ first native-born Black male when he died on Nov. 13, 1967. The Donaldsons were the only Black family until the influx of Black workers to help build the railroad.

Those settlers were not treated with the same respect as Donaldson. One Black family was tolerable, but as more Black people migrated to the area, attitudes changed, Reese noted.

Elder Jordan Sr., born into slavery about 1850, came to St. Pete in 1904. Jordan Sr. married Mary Frances Strobles, a Cherokee who stood more than six feet tall. Strobles was from Rosewood, Fla., a community that was notoriously destroyed in 1923 during a massacre of Blacks by whites.

Jordan Sr. owned considerable property on the south side, including a livery stable and a filling station on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 16th Street. Jordan Sr. and his sons built houses and helped open several businesses in the Black community. He also opened the beach for African Americans and operated a bus line.

In 1925, he saw a need for a gathering place for the growing Black community and built the Jordan Dance Hall, now known as the Manhattan Casino. He built his dance hall on 22nd Street (the Deuces), where people of color came to shop, socialize and conduct business without the stigma of racism tainting every interaction or transaction.

“It became the venue for local Black artists and was a significant stop in what was known as the ‘Chitlin’ Circuit,'” she said. “The Manhattan was to the Black community what the Coliseum was to the white community. The building was designated a historic landmark by the city council in 1994.”

In 1929, after the stock market crashed, Jordan Sr. was one of the few people in the community whose money wasn’t in the banks. To help keep the city afloat, he loaned some of it to the city government, Reese said. Jordan Elementary School and Jordan Park Housing Project are named for Jordan Sr., and a monument in his likeness and honor stands at the southwest corner of the Manhattan Casino property.

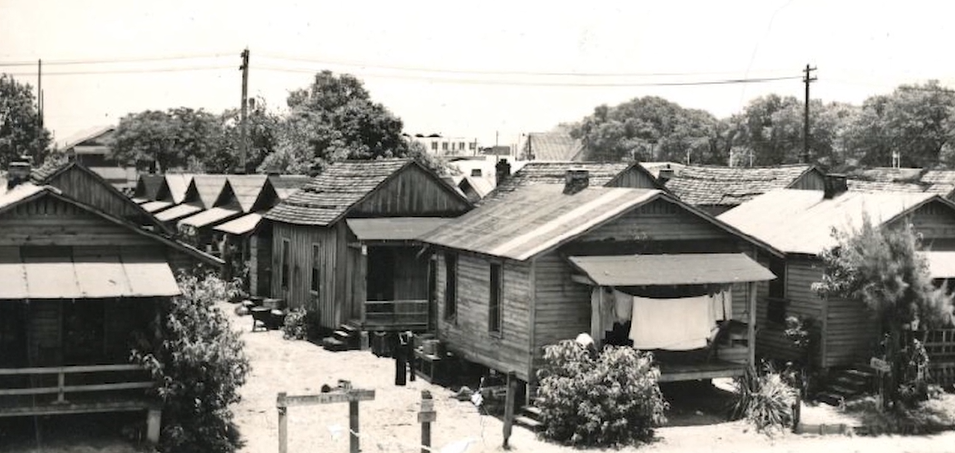

Most African-American communities in the city consisted primarily of dirt roads and unpainted shacks owned by absentee white landlords who were often indifferent to the property and the people who rented it.

The railroad laborers and other Black workers who came after the Donaldsons were forced into circumscribed neighborhoods when settling in St. Petersburg. Often, these neighborhoods were redlined by banks, meaning that mortgage loans could not be obtained or, if available, only at very high rates.

“Black people were relegated to live in certain segregated neighborhoods safely away from the tourists, white neighborhoods, and downtown businesses,” Reese said. “Most African-American communities in the city consisted primarily of dirt roads and unpainted shacks owned by absentee white landlords who were often indifferent to the property and the people who rented it. There were a few exceptions to living in the neighborhoods relegated to Blacks. According to early city directories, several ‘colored’ families lived in what were not traditional-like neighborhoods.

“Over 100 Black workers who helped build the Orange Belt Railway made their home in Pepper Town, located east of what is now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. St. and Third and Fourth Avenue South. The area around Booker Creek along Ninth Street, south of First Avenue South, was initially called Cooper’s Quarters and later became known as the Gas Plant area. It was named for the two large cylinders housing the natural gas supply for the city.”

The third African-American community, Methodist Town, grew around Bethel AME Church and was named for the church.

There was a thriving business district in the Gas Plant area, and it was the home of Davis Academy, the first Black school in St. Petersburg. In 1894, Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded at 912 Third Ave. N. A 1912 Polk City directory listed the location as Third Avenue North and Williams Court. The third African-American community of Methodist Town grew around it and was named for the church.

“It was on a side of town that was generally off-limits unless you were white,” Reese explained.

Most of the money earned by Black workers went to White businesses outside their communities. The result was a damaged ability to build intergenerational family wealth. A study in 2018 revealed that three out of four neighborhoods that were redlined 80 years ago continue to struggle economically. Today, nearly 26 percent of St. Petersburg’s African-American population has income considered below the poverty level.

Next, in this four-part series, we’ll explore the city’s segregated healthcare system and “some” women’s right to vote.