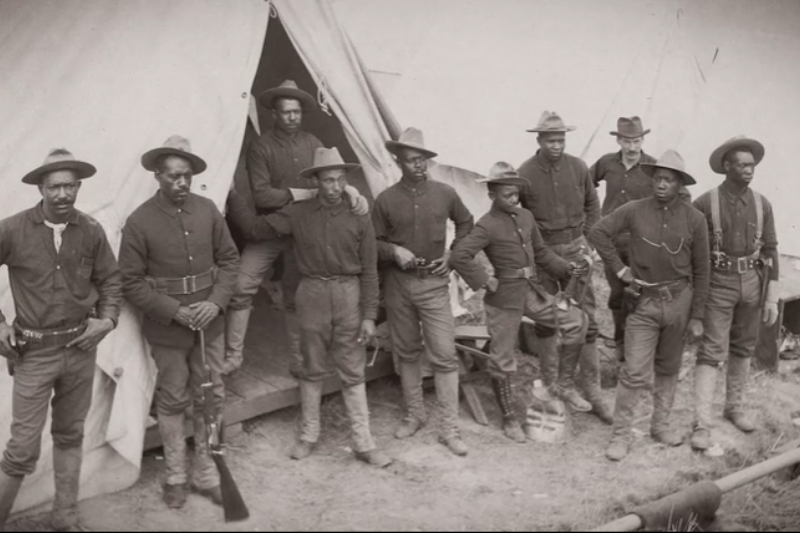

The Buffalo Soldiers were sent to the Philippines as reinforcements.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

The PBS documentary “Buffalo Soldiers: Fighting on Two Fronts” depicts the plight of African-American soldiers in this country as they fought military conflicts abroad and civil rights struggles at home.

In the last installment, we learned about the Buffalo Soldiers’ plight in the Wild West and the horrors Black cadets such as Charles Young endured to attend the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Now, we pick up Lieutenant Young’s journey in the Philippine islands.

When war broke out with Spain in April 1898, Charles Young was stationed at Wilberforce University. Since the war was essentially over in Cuba by July, he couldn’t rejoin the 9th Cavalry to participate in the actions there. He didn’t get to witness the charge of the 10th Cavalry — followed by Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders — on San Juan Hill.

The Buffalo Soldiers were ordered to annihilate the Filipino rebels, led by General Emilio Aguinaldo, the Republic of Philippines’ first president.

During the Spanish-American War, the United States also invaded the Philippine islands and took Puerto Rico and Guam.

“It was a time when the president, the politicians thought, ‘Well, this is our chance to establish an empire,'” said Charles Young’s biographer Brian Shellum.

Philippine leader General Emilio Aguinaldo and his revolutionaries had fought alongside the United States against Spain and found themselves the possession of a new colonial master. The Filipinos, however, wanted their own independence.

“And so, you see that war quickly turning to what’s perceived by the Filipinos as a war against the United States,” said historian and author Greg Shine.

African Americans were divided in response to the U.S. war in the Philippines, and prominent journalist Ida B. Wells argued that “Negroes should oppose expansion until the government is able to protect Negroes at home.” Booker T. Washington agreed and said that “the Philippine islands should be given a chance to govern themselves. Until our nation has settled the Indian and Negro problems, I do not think we have the right to assume more social problems.”

An editorial in a Black-owned newspaper, the Indianapolis “The Freeman,” supported the war, and the debate among African Americans in the U.S. carried over to Black soldiers on the battlefield. Filipino insurgents distributed pamphlets addressed to “the Colored American soldier,” encouraging them to desert, and a small number defected.

“Soldiers like David Fagan decided enough was enough, deserted, and they fought alongside Filipinos against their brethren,” historian Anthony Powell said. “Now they lost the war, and they lost their lives, but they did something that is purely an American principle: liberty and freedom. That’s why they deserted, and I think that is misunderstood by a lot of people because they, as Black men, knew how America treated them at home.”

Charles Young and I Company of the 9th Cavalry arrived in the Philippines on May 16, 1901. Newly promoted to captain, Young’s first mission is to lead the Buffalo Soldiers up the Gandara River to pacify a village called Blanca Aurora.

One of Captain Young’s officers, Sergeant H.W. Nicholas, described the mission in a letter: “We were about 12 days going the 18 miles, off and on the boats, fighting our way up the stream on both sides of the river.”

Drawing close to Blanca Aurora, Sergeant Nicholas is stranded on a reef with the supply boats. Captain Young had the main body of his force divided on each side of the river, fighting his way forward. Previous missions to Blanca Aurora had failed, and many U.S. commanders resorted to scorched-earth tactics in their fight against the Filipino guerrillas. Young understood guerrilla warfare. He pacified the village peacefully, gave them security and supplies, and separated them from the insurgents.

Young’s deft touch was so successful that his commanding officer promised I Company a plum assignment after the war.

“So, they got duty in the beautiful city of San Francisco as a reward for their good service in the Philippines,” Shellum said.

Young and I Company served for another year in the Philippines and fought in the decisive Batangas campaign against General Malvar. The Filipinos would not achieve their independence for another 44 years.

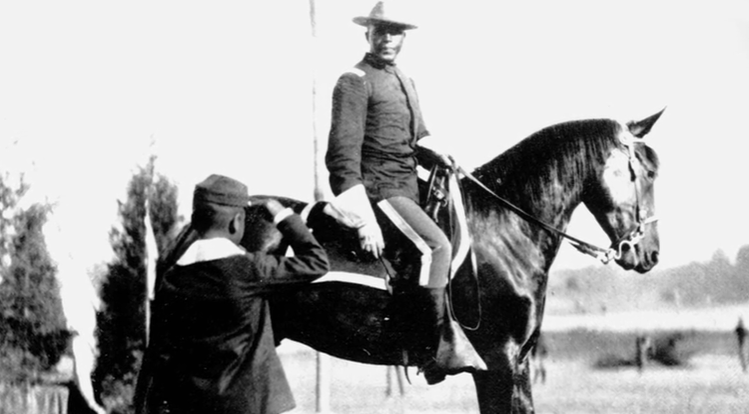

In 1903, shortly after Young and I Company returned to the United States, President Roosevelt visited San Francisco.

“San Francisco planned a big parade down Market Street, and Young was selected to lead two troops of the 9th Cavalry as the honor guard for the president,” Shellum explained.

It was the first time that Black troops had been included in a presidential honor guard.

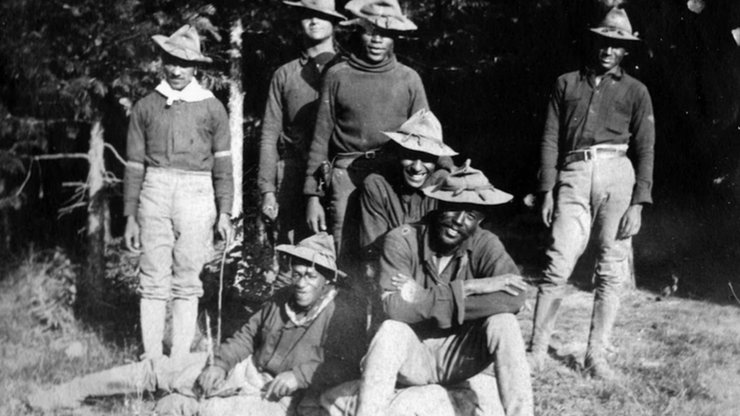

After Roosevelt’s visit, Young and two companies of the 9th Cavalry are dispatched to Sequoia National Park.

Sequoia National Park was established in 1890, and in the fledgling days of the National Park System, U.S. Army troops served as park rangers.

“Charles Young was the first African-American superintendent of a national park, and that was Sequoia National Park,” Powell revealed.

Sequoia had only been established in 1890, and in the fledgling days of the National Park System, U.S. Army troops served as park rangers. They would send troops to the various national parks to make sure that people didn’t homestead or people were not poaching, Powell said.

“Charles Young has many accomplishments,” author and park ranger Shelton Johnson said. “Building the first road to the top of Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the United States, that’s incredibly significant. But under his supervision, the first usable wagon road into Sequoia’s Giant Forest was completed, and more work was done in the summer of 1903 than all the other preceding years combined.”

Young began courting Ada Mills during that summer in Sequoia, whom he soon married in a small, private ceremony. She brought some stability to Young’s bachelor life. He was 40 years old at the time, and she was 24, but she was well-educated and a good match, Shellum stated.

Officers like Captain Young had long been allowed to bring their wives to postings. Starting in the late 19th century, enlisted men could bring their families, too.

“And so there now are communities that develop around these Buffalo Soldier outposts,” said Professor Quintard Taylor, Ph.D., University of Washington.

The Buffalo Soldiers were often some of the first Black people in predominantly white settlements, creating the opportunity for connection across communities. As Young argued in an impassioned speech in 1903: “We are part and parcel of the body politic of the United States. All we ask is a white man’s chance. Will you give it?”

Perhaps the most notorious incident of racial injustice involving the Buffalo Soldiers occurred in the summer of 1906 when the First Battalion of the 25th Infantry transferred to Brownsville, Texas. On the night of Aug. 13, shots rang out, and a white bartender was killed. Locals claimed that they witnessed Black soldiers firing weapons. White officers attested that the soldiers had been in the barracks, and none of their weapons had been fired.

Perhaps the most notorious incident of racial injustice involving the Buffalo Soldiers occurred in the summer of 1906 when the First Battalion of the 25th Infantry transferred to Brownsville, Texas.

Powell explained that 167 Black soldiers were discharged without honor for a crime that they didn’t do.

“Many of those soldiers had served with distinction for 20 years,” Quintard said.

One of those soldiers was First Sergeant Mingo Sanders, who was partially blinded during his service in Cuba and whose commanding officer called him “the best non-commissioned officer I have ever known.”

First Sergeant Mingo Sanders, who was partially blinded during his service in Cuba, was discharged after the Brownsville affair without honor for a crime that they didn’t do.

“It was Theodore Roosevelt who ordered this 25th Infantry discharged after the Brownsville affair,” Powell said.

The African-American community, which had supported Republicans since the Civil War, was outraged, but Roosevelt refused to budge.

“All of the evidence showed that these men were innocent, but because Roosevelt wanted to make sure that his Southern, you know, constituency was OK, that’s what he did to those men,” Powell said.

Young faced a more subtle form of discrimination as a Black officer in a white officer corps. The army was preoccupied with keeping Young in what they felt were appropriate assignments for a Black officer, Shellum said. As he rose in rank to captain and major, this became an increasing problem.

In 1904, the army solved this problem by assigning Captain Young as military attaché to Haiti and the Dominican Republic. He served for three years, gathering intelligence to help the U.S. plan for a possible military intervention on the island.

By 1912, the army had assigned Young as military attaché to Liberia, a West African country founded in 1822 by free and formerly enslaved Black Americans. The descendants of these founders called themselves Americo-Liberians and ruled over a large indigenous population.

By 1912, the army had assigned Young as military attaché to Liberia, a West African country founded in 1822 by free and formerly enslaved Black Americans.

“Can you imagine, in 1912, you’re a Black man, and you’re going back to Africa, and he finds this upside-down world where former African Americans have gone, and they’ve kind of reproduced plantations, and they’re treating their own indigenous people terribly — as slaves, practically,” Shellum averred.

Young’s mission was to train the Liberian Frontier Force, which was drawn from the indigenous people. He was assisted by three other Black U.S. Army officers.

At first, he was all behind the mission, Shellum explained, but over the three years he was there, he began to doubt the motives of the Americo-Liberians who were trying to suppress the indigenous people.

Charles Young had brought his wife, Ada, and their two young children to the post, but they had to be evacuated due to the lack of safe water and food.

Liberia in 1912 was a dangerous place for Westerners. Young had brought his wife, Ada, and their two young children to the post, but they had to be evacuated due to the lack of safe water and food. Young developed blackwater fever, a malignant form of malaria, which will come back to haunt him later in life.

In 1916, Young and the Buffalo Soldiers fought in the last great cavalry campaign in the West.

In 1916, Charles Young and the Buffalo Soldiers fought in the last great cavalry campaign in the West against warlord Pancho Villa.

“Pancho Villa was a warlord in Northern Mexico at the turn of the 20th century,” Millner said, “and our relationship with our southern neighbor was probably even more tumultuous than the one we’re experiencing in this generation.”

Villa’s bandits raided Columbus, N.M., and shot up the town, killing 18 Americans. The United States responded by sending an expedition that, at its height, reached 10,000 American soldiers into Northern Mexico.

Young had been promoted to major while stationed in Liberia, and the army transferred him to the 10th Cavalry to serve under General Jack Pershing in the Punitive Expedition. Early in the expedition, on April 1, 1916, Major Young and the 10th Cavalry surprised a group of 150 Villistas near the outskirts of Agua Caliente.

The troopers of the 10th Cavalry dismount and attack, forcing the Villistas to retreat behind a ridge.

“So Young used the machine gun troop as covering fire to pin down the enemy force, and he just overwhelmed them,” Shellum said.

Under covering fire from the machine gun troop, Young directed a flanking maneuver, forcing the Villistas to retreat in disorder. He then led a pursuit of the Villistas in a running battle until his men and horses were overcome by exhaustion.

“It’s the first time that I know of that Americans used machine guns in covering fire, and it caught the eye of General Pershing,” Shellum said.

Shellum asserted that the Punitive Expedition saw the advent of a lot of what we know as modern warfare beyond machine guns. It was the first use of trucks for transporting supplies. It was also the first use of aircraft used for reconnaissance and to carry messages back and forth.

It signaled the end of cavalry and a new era of mechanized modern warfare.

Despite a spirited campaign — at one point, the 10th Cavalry even disguised themselves as Mexican bandits — after nearly a year in Mexico, the U.S. Army gave up the chase. They never found Pancho Villa.

Despite a spirited campaign — at one point, the 10th Cavalry even disguised themselves as Mexican bandits — after nearly a year in Mexico, the U.S. Army gave up the chase. They never found Pancho Villa.

However, Young received high praise from General Pershing. Young is promoted to lieutenant colonel, and Pershing put Young on his list of officers to command future brigades during World War I.

“Charles Young was slated to become a brigadier general,” Powell said. “They couldn’t have him in command of a division.”

Shellum said if Young were used in Europe the way he wanted to, he would have been commanding Black troops but led by white officers. He added that white lieutenant colonels, white majors, white captains, white lieutenants, and at the time, that was a problem for the War Department.

A medical examination board found that Young had a range of health problems related to his long service in the army.

“He was about 52 years old,” Shellum said. “He’d spent a lifetime as a cavalry officer in the saddle, and he had blood in his urine. He’d had blackwater fever, and that was working on his kidneys.”

Due to Young’s abilities and the army’s need for the coming war in Europe, another promotion board recommended waiving the medical problems. That recommendation went forward to Washington, so then it became a political decision, Shellum said.

Charles Young made one last attempt to prove he was fit to serve. He saddled up his favorite horse, Blacksmith, and rode from his home in Wilberforce, Ohio, to the steps of the War Department in Washington, D.C.

“President Woodrow Wilson, who was the first Southern Democrat elected to the White House since the Civil War, simply arranged it so that Charles Young was retired before he could assume that kind of position of command,” Millner said. “Clearly, it was a racially motivated decision, politically motivated, influenced by the racism of President Wilson and Secretary of War [Newton D.] Baker.”

Young made one last attempt to prove that he was fit to serve.

“He saddled up his favorite horse, Blacksmith, and decided he was going to prove his fitness by riding from his home in Wilberforce, Ohio, to the steps of the War Department in Washington, D.C.,” Shellum said.

Young rode nearly 500 miles over two weeks, and despite wearing his army uniform, he was sometimes refused service at white-owned hotels along the way. By the time Young arrived in Washington, D.C., his ride had been covered extensively in the press, putting pressure on Secretary of War Baker to reverse his decision.

“Baker essentially promised him a command if he’d go away,” Shellum said. “Young took him to his word, and he went back to Ohio, and Baker never carried through with his promise.”

Young never got to serve in World War I. To show the hypocrisy of the U.S. Army, Shellum pointed out they recalled him to active duty after the war and asked him to return to Liberia.

As Young’s old friend W.E.B. DuBois asked, “If Charles Young’s blood pressure was too high for him to go to France, why was it not too high for him to be sent to even more arduous duty in the swamps of West Africa?”

Essentially, they were sending Young back to Liberia to die, Shellum said, adding that he loved the army so much he couldn’t say no.

Young was on a mission to the interior of Nigeria when he was struck again by blackwater fever. He showed up at a hospital in Lagos, Nigeria, in poor shape and died on Jan. 8, 1922.

“Ada Young wrote letter after letter to the War Department saying that she wanted Charles Young’s body brought back to the United States,” Shellum said.

A year after his death, Charles Young’s body was disinterred and brought to Washington, D.C. Black citizens lined the streets to get one last look at his casket as it rode by trailed by a cavalryman’s horse with boots in the stirrups backward, as is tradition for a cavalry commander.

A year after his death, Young’s body was disinterred and brought to Washington, D.C. Black citizens lined the streets to get one last look at Charles Young’s casket as it rode by, Shellum said, trailed by a cavalryman’s horse with boots in the stirrups backward, as is tradition for a cavalry commander.

Young was finally laid to rest with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. In 2022, the U.S. Army awarded Colonel Charles Young the star he was promised, making him the first Black Brigadier General.

Although never officially called “Buffalo Soldiers,” Black troops served bravely in segregated regiments in World War I and II. The army’s policy of racial segregation finally ended in July 1948 when President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order abolishing racial discrimination in the U.S. Armed Forces, but this did not really go into effect until after the Korean War.

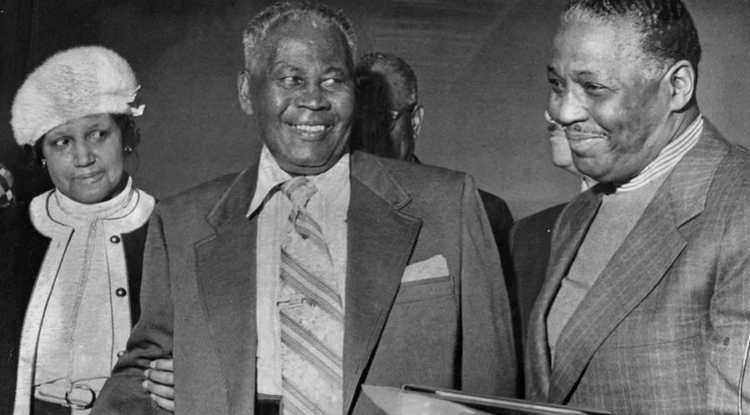

In 1972, Dorsie Willis, (middle) the last surviving member of the Brownsville affair, was pardoned by President Nixon and given $25,000 in back pay.

Black and white soldiers did not fight in integrated units until the Vietnam War, and it wasn’t until 1972 that Dorsie Willis, the last surviving member of the Brownsville affair, was pardoned by President Nixon and given $25,000 in back pay.

All historical photos used in this article were taken from the documentary “Buffalo Soldiers: Fighting on Two Fronts.”