Wanda Stuart shares her childhood antics of living by Laurel Park.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is an ongoing USF research study that addresses the erasure of historic Black cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area. Awarded a USF Blackness and Anti-Black Racism grant in 2020, it consists of faculty, staff, and students from multiple disciplines across USF St. Pete and Tampa campuses.

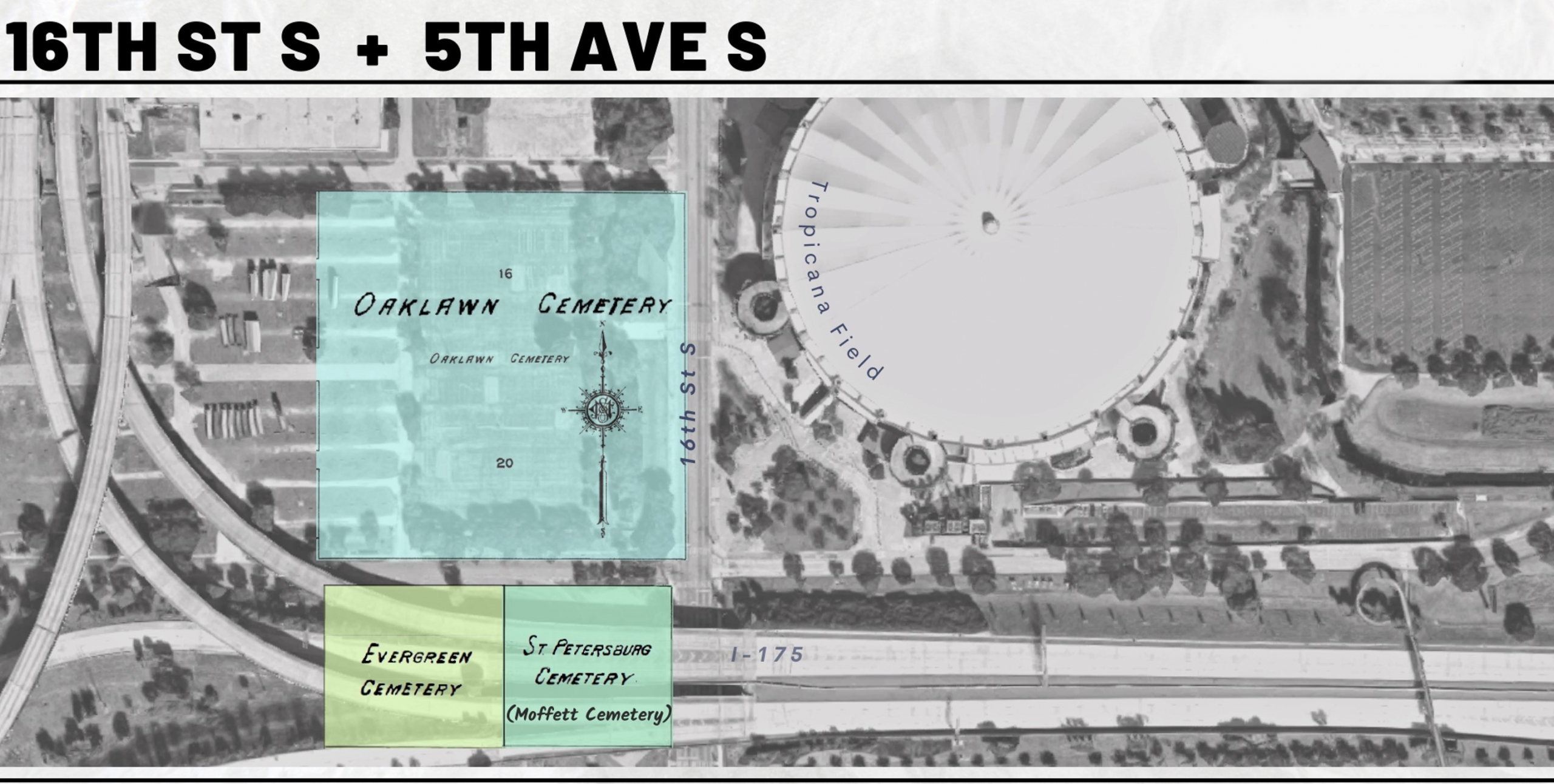

The project focuses on activities to identify, interpret, preserve, record, and memorialize previously unmarked, erased, abandoned, and underfunded African-American burial grounds in Florida, with a focus on Tampa’s Zion Cemetery (located beneath Robles Park Village) and St. Petersburg’s Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries (found beneath a Tropicana Field parking lot and I-275).

One aspect of the African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is recording oral histories of those who remember or are related to those lost to time.

Wanda Stuart

Wanda Stuart grew up in south St. Petersburg, and during her walks to 16th Street Junior High School, now known as John Hopkins Middle School, she never really noticed the nearby cemeteries. She did, however, recall the sour smell emanating from the gas plant.

“We were in the vicinity of Laurel Park and the gas plant,” she said. “You could smell the horrible odor coming from the gas plant. I don’t know why I remember the smell, but I can remember the smell. I can remember the wall. I can remember friends jumping the wall. You know, it’s like, okay, can I really remember the cemetery? I know it was there, but it was just like, ‘Okay, this is a cemetery. You just walk past it.'”

Young Stuart lived with her grandmother, Bonnie Elizabeth Caruthers, at 330 18th St. S and recalls the surrounding area and its well-known establishments such as the Perkins House, 20th Street Church of Christ, various retailers, a trailer park and a community grocery store.

Stuart’s grandmother bought the house on 18th Street, which was pretty progressive because women didn’t have many rights back then, and Black women even less.

Stuart said she was raised as a Christian, so music in the house she grew up in was not readily available. She would listen to the “Ed Sullivan Show” at night and go to church and listen to and participate in a cappella singing, but in terms of jazz music and R&B, she wasn’t allowed to listen, let alone go to the Manhattan Casino.

“Although my mother, who was a radical, she got a job working at the Manhattan Casino as a waitress,” Stuart said. “So, she sort of swayed from the normal things. So, I can’t say that my family could not participate. It was just that certain ones of my family were not allowed to do certain things, and I was one of them.”

Even though there were dances at Campbell Park, Stuart would not be permitted to go. Yet her friends found a way to see her, as they used to jump the neighboring wall to sneak a visit to Stuart at her house.

“My grandma had a cement wall, and that cement wall divided our house from the apartments behind our house,” she recalled, noting that those apartments were Laurel Park. “They would climb the wall, or I would try to climb the wall and get over to visit them.”

When Stuart first heard about the cemeteries being erased, she wondered if she had any family buried in them apart from George Covington, her stepfather. Yet she does not know exactly where his remains are.

“My stepfather is in Lincoln Cemetery, and we can’t find his grave to this day,” she said. “It’s an unmarked grave. And I was just out there about two weeks ago, trying to find his grave…”

Her younger brother would like to find his father’s grave. Covington was buried in the 1970s and killed in a passion crime by her mother.

Stuart’s mother — a victim of domestic abuse — served seven years of a naturalized sentence in prison while Stuart moved to Maryland with her aunt to finish high school. It was mainly to keep the teenage Stuart out of the newspapers following the crime.

“I actually have documentation and letters of people who were vocal for helping her and how she went through the whole prison system,” Stuart said.

Above all, Stuart believes that people must remember their roots and their own families’ histories and hold on to any scraps of memorabilia they can to cement a connection to the cherished past.

“I say dig out those old documents, receipts — I’m using receipts, clothing receipts, funeral programs, old driver’s license of my grandfather’s, old barbering license of my grandfather’s that have dates on them so that it tells me where my family was,” she said.

“Take out that information, [and] share that with your family at your family reunions. Make sure that someone in your family knows about the family’s history because it’s important to be passing it along.

“We shouldn’t see the vicinages of our people not educated in this time when education was such a great opportunity for us. We had to pretend that we couldn’t read. Now we don’t want to read. We don’t understand the value behind reading. All we want to look at [is] our cellphones. Pick up a book; read a book; learn something. And one of the first places to learn is about yourself [and] who you are because it contributes to your success. It helps.”

Dr. Antionette Jackson interviewed Wanda Stuart on March 7, 2022.

Hi Frank

This article is informative and as you know based on the work being done by the USF African American Burial Ground Team. Additional information about the project and access to the work being done by the team is published at USF Digital Commons–https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/african_american_burial_grounds_ohp/

Any additional project inquiries may be directed to Dr. Antoinette Jackson, African American Burial Ground Project leader/(PI) at: atjackson@usf.edu

Thank-you!

Hello, My name is Vanessa and I am the president of Lincoln Cemetery Society. Is there a way to pass on a message to Wanda concerning her step-father? Our email is lincolncemeterysociety@gmail.com I found where her step father’s plot is located in Lincoln Cemetery and I would like to connect with her so I could show her the plot and the records. I appreciate it and thank you for what you’re doing.

Sincerely,

Vanessa Gray

lincolncemeterysociety@gmail.com