Dr. Kemesha Gabbidon, a University of South Florida researcher and Precshard Williams, Prevention and Sexual Health Program coordinator at Metro Inclusive Health, are working to remove the stigma around HIV and AIDS.

BY J.A. JONES, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Dr. Kemesha Gabbidon, a researcher at the University of South Florida who studies youth sexual health and HIV stigma, said for her work to accurately capture what’s happening in society, she studies not just the numbers but also experiences of community members.

The outcomes from her research determine where government funding goes to address issues impacting health disparities and HIV in a community.

“Direct service [workers] and practitioners are the boots-on-the-ground folks that overlap with whatever my and other researchers’ findings are, “she shared recently on a 99 Jamz radio show discussion on sexual health, stigma and HIV. “Our findings are really implemented by those in service and practice.”

One of those boots-on-the-ground workers is Precshard Williams, Prevention and Sexual Health Program coordinator at Metro Inclusive Health. Williams joined Gabbidon on the show to discuss his work, the Pinellas EHE (Ending HIV Epidemic) initiative, and the role of sexual health and stigma in the fight against HIV and AIDS.

Williams oversees a team that works out in the community doing HIV and Hep C testing and offering education and counseling. He shared how those working on the prevention side use the information that researchers such as Dr. Gabbidon uncover. This information, said Williams, “sometimes called epi-data, epidemic data, helps me map out where we’re going, who we’re going to look for, who we’re going to reach — all the way down to the messaging and the marketing.”

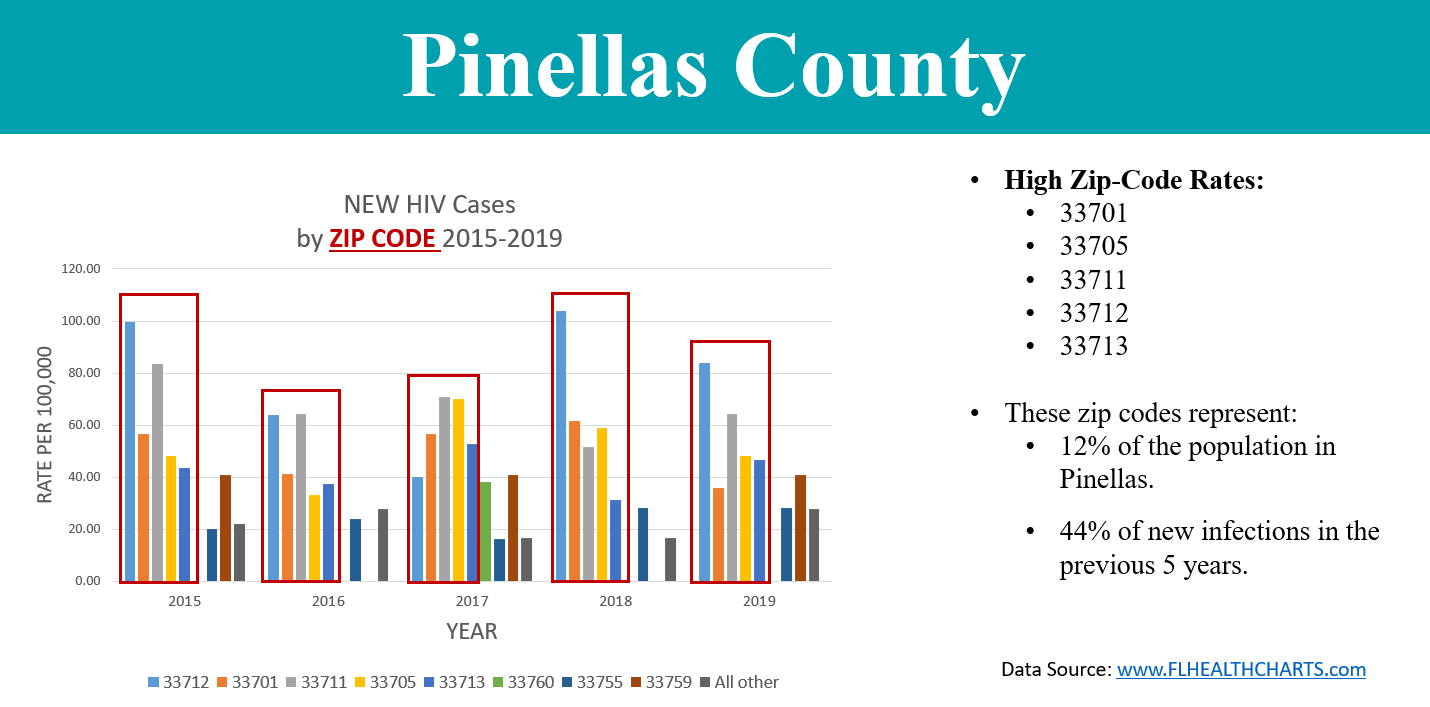

His team also works with community partners to make sure that life-saving information is diffused out into communities, especially those that are affected most. Current data helped the Florida Department of Health and #PinellasEHE pinpoint high-diagnosis areas to target, specifically five zip codes in St. Pete: 33712, 33701, 33711, 33705 and 33713 that have the highest rate of HIV in the county.

But, said Williams, “Putting funding out didn’t just meaning let’s just drop some money in this area, it meant being more strategic about how we were going to use that funding to be able to bring those numbers down for HIV.”

#PinellasEHE’s long-term goals include reducing HIV by 75 percent within five years and by 90 percent within 10 years. By doing that, affirmed Williams, “Basically we will be able to end HIV.”

Providing education in those zip codes is a way to combat that stigma; also vital, he noted, is providing testing to make sure that people know their status.

“The goal in the testing is to help people know their status: if they’re negative, how can we keep them negative; if they’re positive, getting them on treatment, and linking them to the services that they need to make sure that they can reach viral suppression.”

Viral suppression indicates that those diagnosed with HIV are on treatment and can’t pass it to anybody once they’re virally suppressed. That, in turn, Williams explained, brings down the viral load in the community.

Gabbidon clarified the difference between having HIV and its more deadly relative, AIDS. “When we talk about incidence, that’s the amount of new cases, the people that are just being diagnosed with HIV within a time frame. So, if you are diagnosed with HIV, ultimately, what we would prefer is for folks to never acquire AIDS.”

AIDS is referred to as the tertiary or last stage of having an HIV infection, but, said Gabbidon, it’s not the same as HIV. While the same virus causes them, one can live with HIV without developing the more advanced stage, which is AIDS. One doesn’t automatically have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome just because they are diagnosed with HIV.

Gabbidon noted that more people who are acquiring HIV are living with the illness and are more likely to succumb to another life-impacting or health event rather than dying of AIDS. “And that’s the goal for people who are diagnosed — we want them to have long, healthy lives.”

Williams feels that stigma has played a significant part in the increase of HIV diagnoses in the area. “I feel that stigma has really set us back. If I could just compare it to, let’s say, COVID; COVID came around, we didn’t know much about it, our responses were really just based off of what we were learning at the time.”

But with HIV, there was a reactionary response. “When it first came out, it was described as a gay disease. So, we got a lot of people thinking that this was just a gay disease and only gay people can get it.”

Added to other issues impacting Black communities — poverty, homelessness, drugs — regional issues have played a factor.

“Here in the south, it’s a little different,” Williams noted. “Stigma is just so difficult to combat at times because of the lack of knowledge and the lack of understanding of what we’re up against.” Even after Ryan White, a young white child, and Magic Johnson, a married sports star, were diagnosed, “unfortunately, what wasn’t changing was the stigma.”

Fear over the disease turned to ignorance, as “harsh” messaging was used to scare people into being safer. Today, Willams said, advocates, prevention experts, and researchers are coming at it differently, letting people know that with testing and treatment, people can lead normal lives.

But Florida laws also add to stigma, he noted. While some may feel that current laws mandating that one disclose their status if they have HIV help ensure safety, Williams notes, “We’re literally criminalizing and locking people up for what they have inside of their body.”

Gabbidon added that while current treatment can decrease the viral load to undetectable, meaning that it’s untransmittable, people are still being marginalized, which in turn marginalizes entire communities.

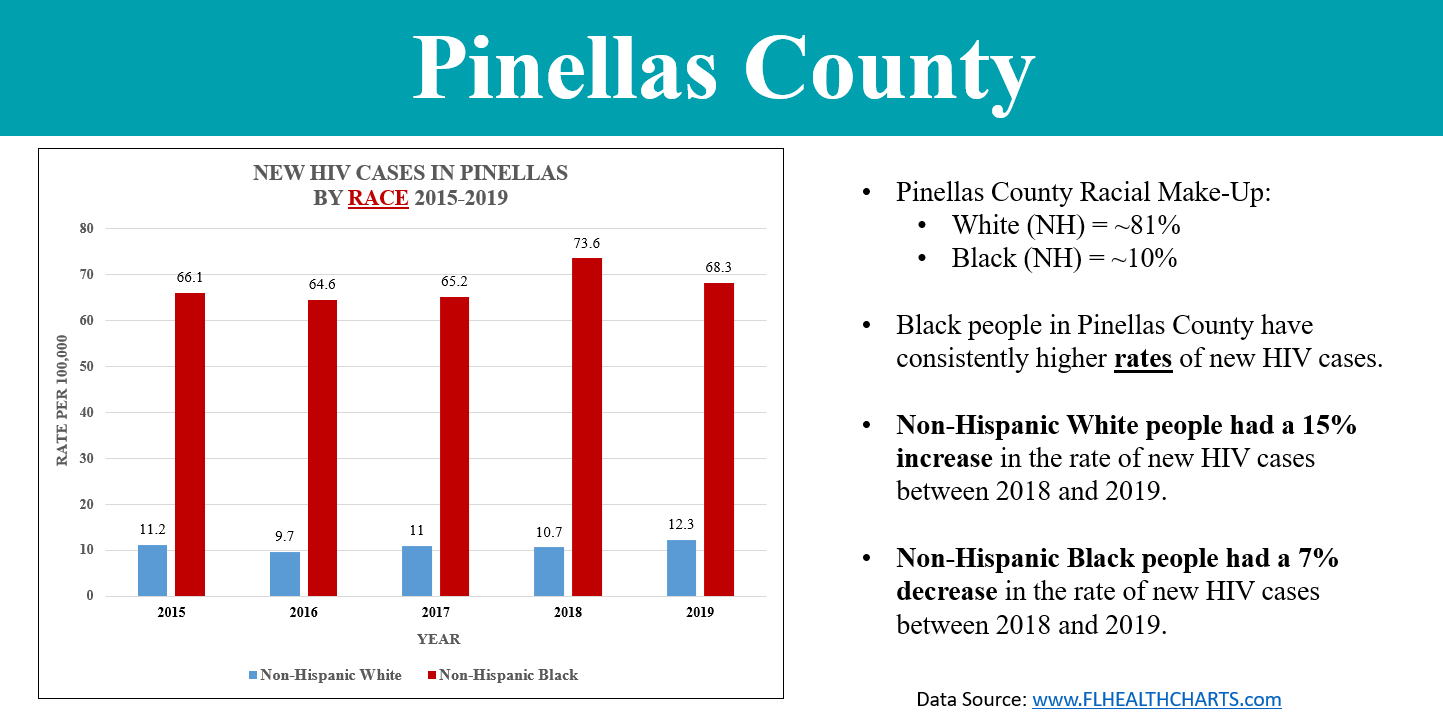

“So that’s why we see certain populations experiencing higher rates of HIV; it has less to do with their behavior and more to do with how we isolate them, how we ‘other’ them as communities.”

She noted that Black and Brown people, the working class, and the LGBTQ+ community often have lower access to resources and are treated differently by society. In doing so, those communities are marginalized, “which means we are not providing the kind of resources, the kind of funding, the kind of education that’s needed.”

To reach J.A. Jones, email jjones@theweeklychallenger.com