Thursday, Nov. 3, Dr. Antoinette Jackson and her team presented their findings on the erasure of Black cemeteries in the Gas Plant area at the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg’s Center for Health Equity.

BY NICOLE SLAUGHTER GRAHAM, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Nov. 3, marked two years to the day that Antoinette Jackson, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Department of Anthropology at the University of South Florida, asked a question that would spur a nationally recognized project.

“Why is it that we’re just now learning that there are people buried under I-275, under the parking lot of Tropicana Field?”

One year prior, a historic cemetery had been found under an apartment complex in Tampa.

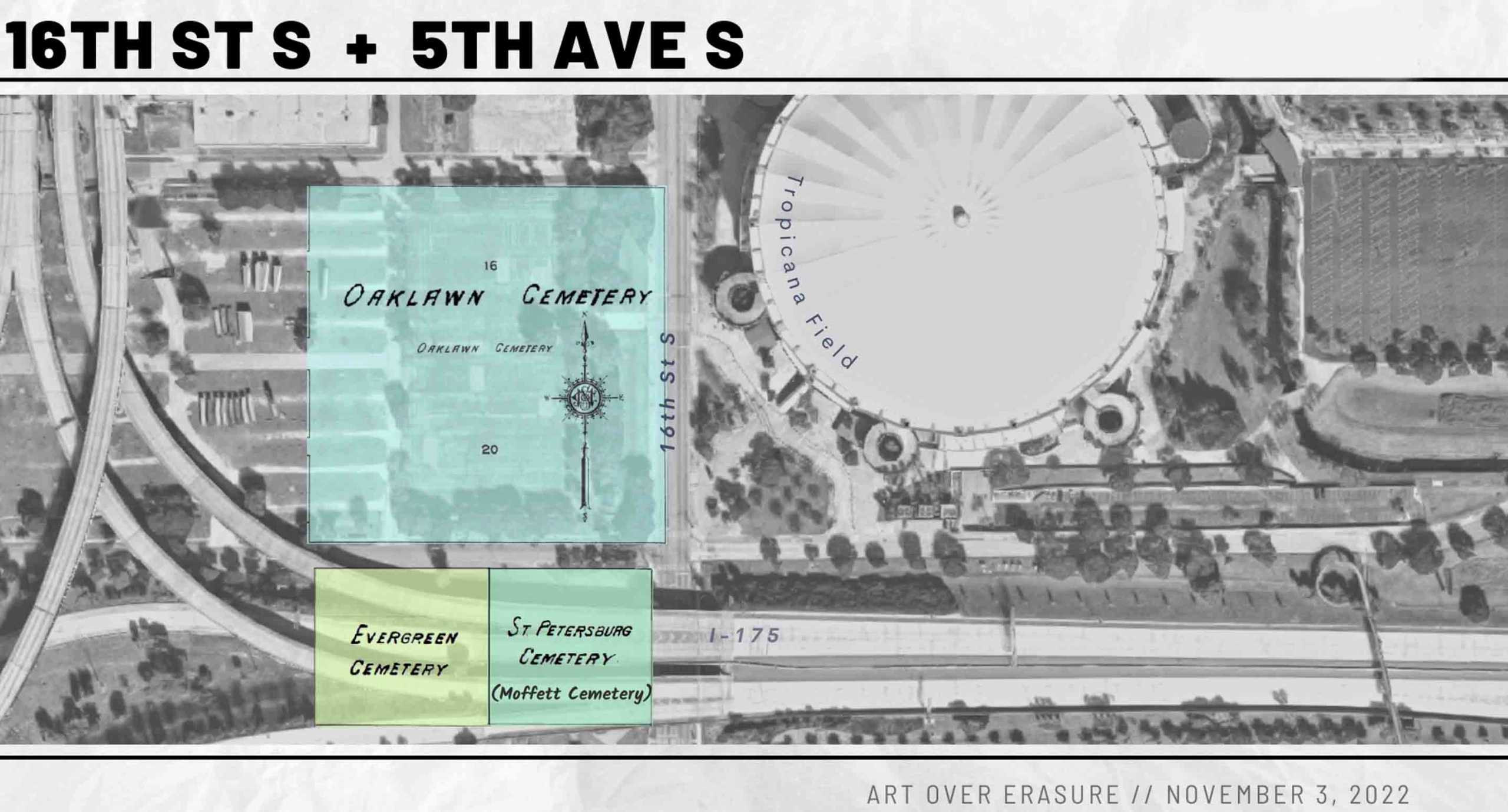

The unknown bothered Jackson. She couldn’t understand why this critical piece of history was a question mark. Whether or not African Americans were buried under Tropicana Field — and who they were — should be known. She wanted to understand why family members did not know the whereabouts of their ancestors, those who were at one time buried in the Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries.

Walter Jennings and Dr. Antoinette Jackson

And so, Jackson, along with a team of researchers, community members, artists and volunteers, started looking for answers. Last Thursday, Nov. 3, the group presented their findings to a crowd of people for the “Art over Erasure” event at the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg’s Center for Health Equity.

Walter Jennings, creative consultant to the project and spoken word artist, kicked off the evening by providing the structure for the event, which included three parts: an overview of the African American Burial Grounds Project (AABGP), the history of African-American cemeteries in the Bay area and information on the Black Cemetery Network.

Each part includes information from Jackson and her team on their findings, performances by spoken word artists and stories from the community. Jackson and USFSP Special Collections Librarian David Shedden provided an overview of the information they found regarding the Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries — all of which were paved over when Tropicana Field and the interstate were built.

Jackson referred to the paving over of Black cemeteries, and therefore Black history, as “levels of erasure.” Shedden further illustrated the layers through his timeline of events that effectively rendered the cemeteries forfeited by the larger St. Petersburg community.

1926 – City of St. Petersburg officials decided to condemn and close the Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries, as they were deemed in a state of disrepair.

“The city promised to move the graves to the newly opened Lincoln Cemetery for African- American burials,” Shedden said.

Mere months after the cemeteries were condemned, the curved road that is still near the interstate at Tropicana Field on 16th Street South was paved on top of Moffett Cemetery.

“Almost exactly 50 years later in 1976, the interstate would be built directly above that curved road and the former Moffett and Evergreen cemeteries,” Shedden continued. “On two occasions during the construction of the interstate, it was found that not all of the graves had been moved.”

1949 – The Royal Court Apartments, later named Laurel Park, were built on top of the Oaklawn Cemetery site.

1953 – An African-American youth center, complete with a swimming pool, was scheduled for construction on top of what was the Evergreen Cemetery. Community leaders, including Rev. Ben Wyland and Monroe McRae (McRae Funeral Home), were a part of the planning process. Within the process, they’d planned to have the remaining graves removed from the cemeteries. At the last minute, city officials changed their minds, and the project was abandoned.

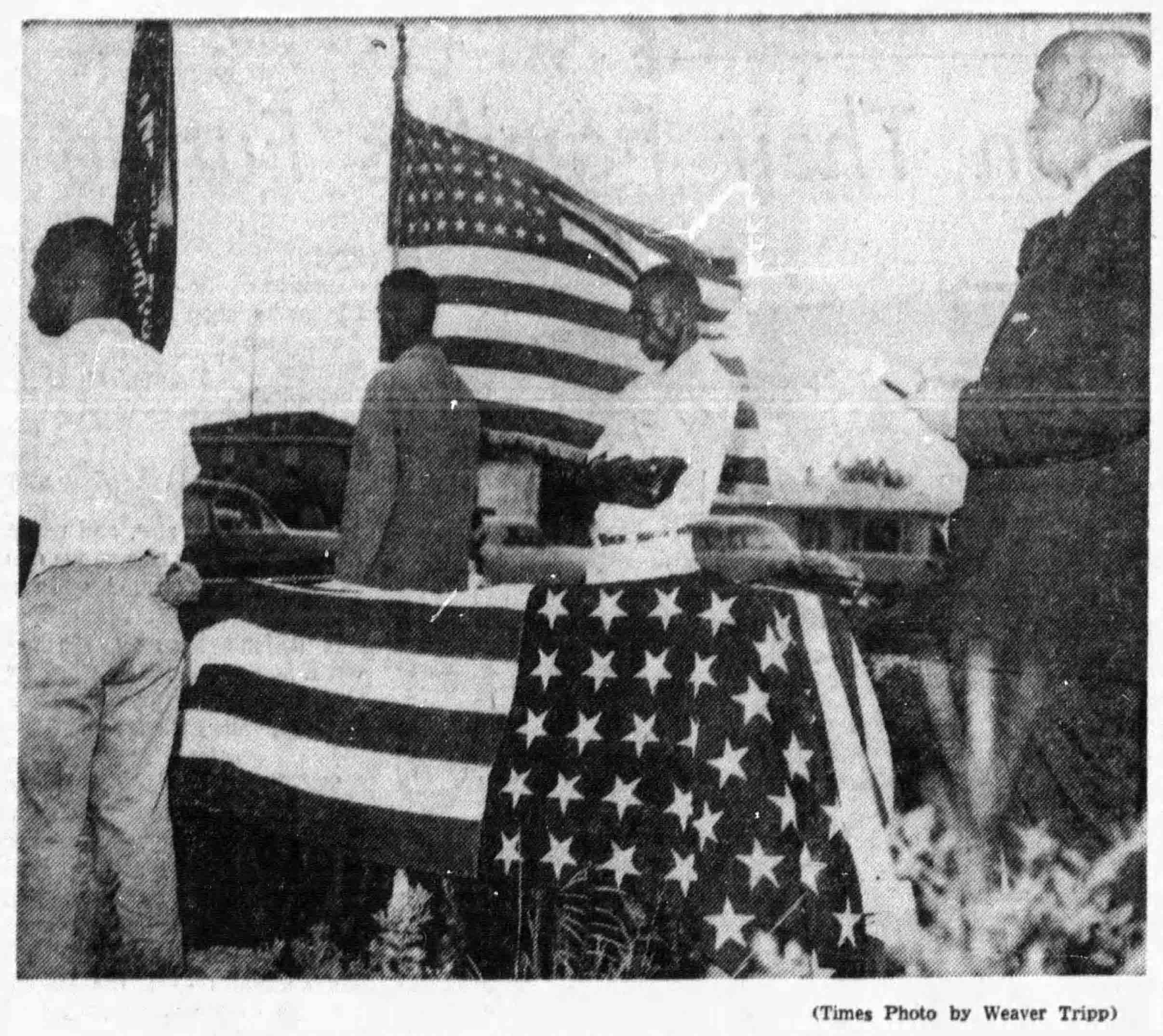

1958 – The staff of the McRae Funeral Home took it upon themselves to move the remaining accessible graves to Lincoln Cemetery. Within Lincoln Cemetery, a special section was dedicated to those transferred from Evergreen. Shedden said it was named “Removals from Evergreen.”

“Graves moved to Lincoln Cemetery included an African-American Civil War veteran by the name of John S. Shorter.”

In his research, Shedden found a photograph from 1958 in which a small group of family members held a service for Shorter before his body was re-buried in Lincoln Cemetery. In the photo, Shorter’s great-grandson — wearing glasses, a white shirt and what appear to be white pants — stands in the middle, arms crossed, looking down at the casket.

Graves moved to Lincoln Cemetery included African-American Civil War veteran John S. Shorter.

In the 1960s through the 1980s, the interstate and Tropicana Field were built, solidifying one of the cemeteries’ final layers of physical erasure.

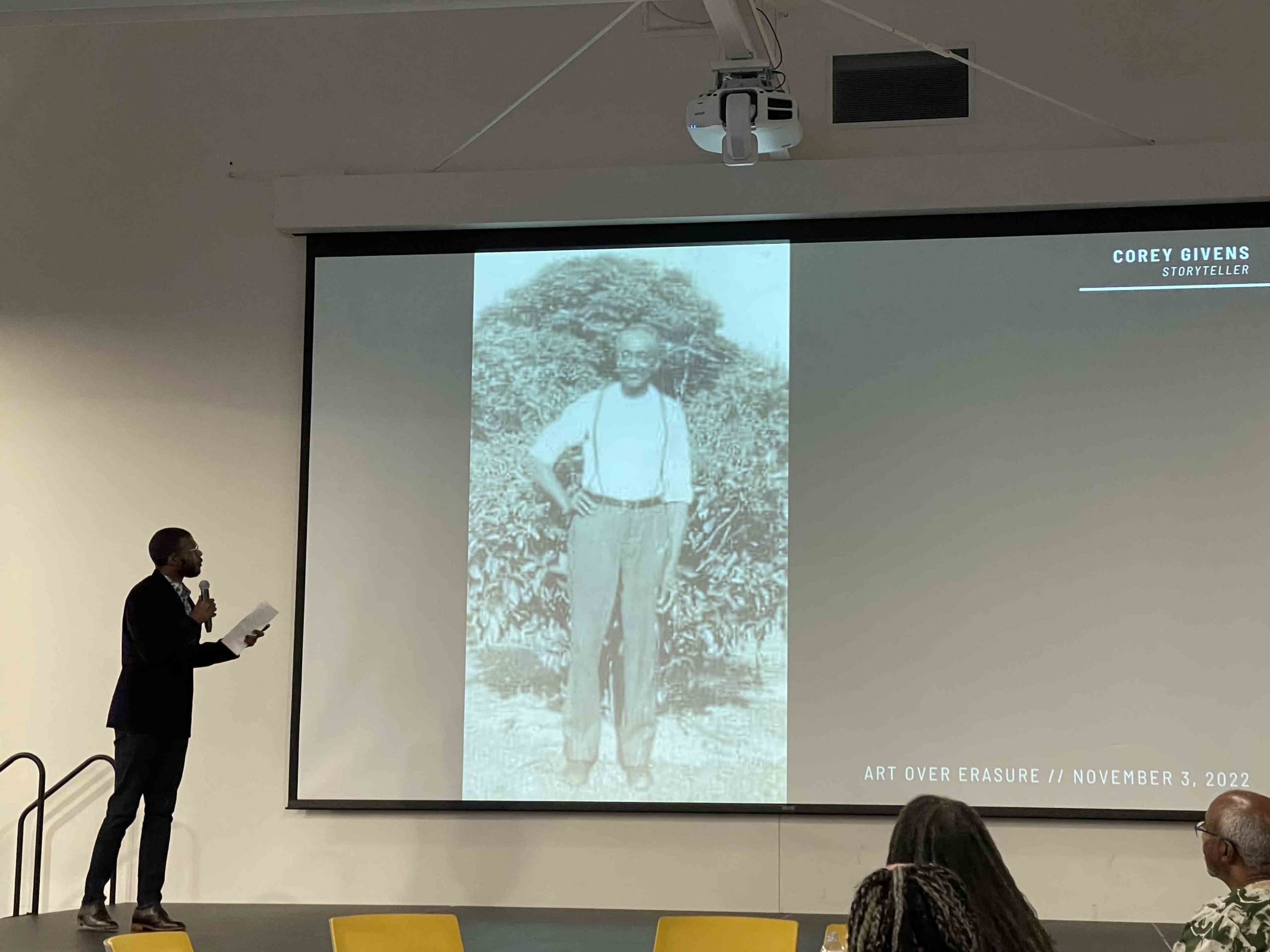

Shedden’s timeline demonstrates the city’s intentional erasure of an integral part of Black history. Now, descendants such as Wanda Stewart and Corey Givens Jr., both of whom told stories of their ancestors, do not have access to the grave sites of their family members who died during this time period.

This phenomenon of erasure isn’t just limited to St. Petersburg, Tampa or even Florida, said Jackson. “This pattern of erasure has been repeated all over the country.”

That, she said, is why this local project turned into a national endeavor, culminating in the creation of the Black Cemetery Network. The website operates as a hub and database where anyone can access information, history, and artifacts on Black cemeteries across the country.

Corey Givens Jr. told stories of his ancestor and said he does not have access to the grave site of his family members who died during this time period.

People can also add information if they have it. Those interested in researching the Black cemeteries in their communities can access a wealth of resources to replicate Jackson’s team’s process.

The event’s impact was made greater by the spoken word and visual artists who contributed their voices and their work to the evening. Spoken word artists C. C. Clark, Shenoah Washington and MIS Wright, performed powerful pieces on the impact of the erasure of Black history through the neglect of Black cemeteries.

Visual artist Lakeema Matthew’s “Our Lost Roots” depicts the circle of life in which death can honor the sanctity of life no matter the color of one’s skin while living. In an Instagram post, Matthews said, “Multiple West African Adinkra symbols have been incorporated in the piece to add more depth to the message of our roots not being lost or forgotten, however, a positive stand of hope. Despite the deceased being disturbed and disrespected with the building atop the sacred burial grounds that numerous melanated people lay to rest.”

The work, Jackson said, is far from over. Part of the purpose of the Art Over Erasure event was to bring awareness to the fact that much is still unknown about St. Petersburg’s intentionally “forgotten” Black cemeteries, and she’s calling on descendants and researchers to come forward to help piece the puzzle together.

Have information on the Evergreen, Oaklawn or Moffett cemeteries or want to learn more about how you might participate in the African American Burial Ground Project? Contact Dr. Antoinette Jackson at atjackson@usf.edu.